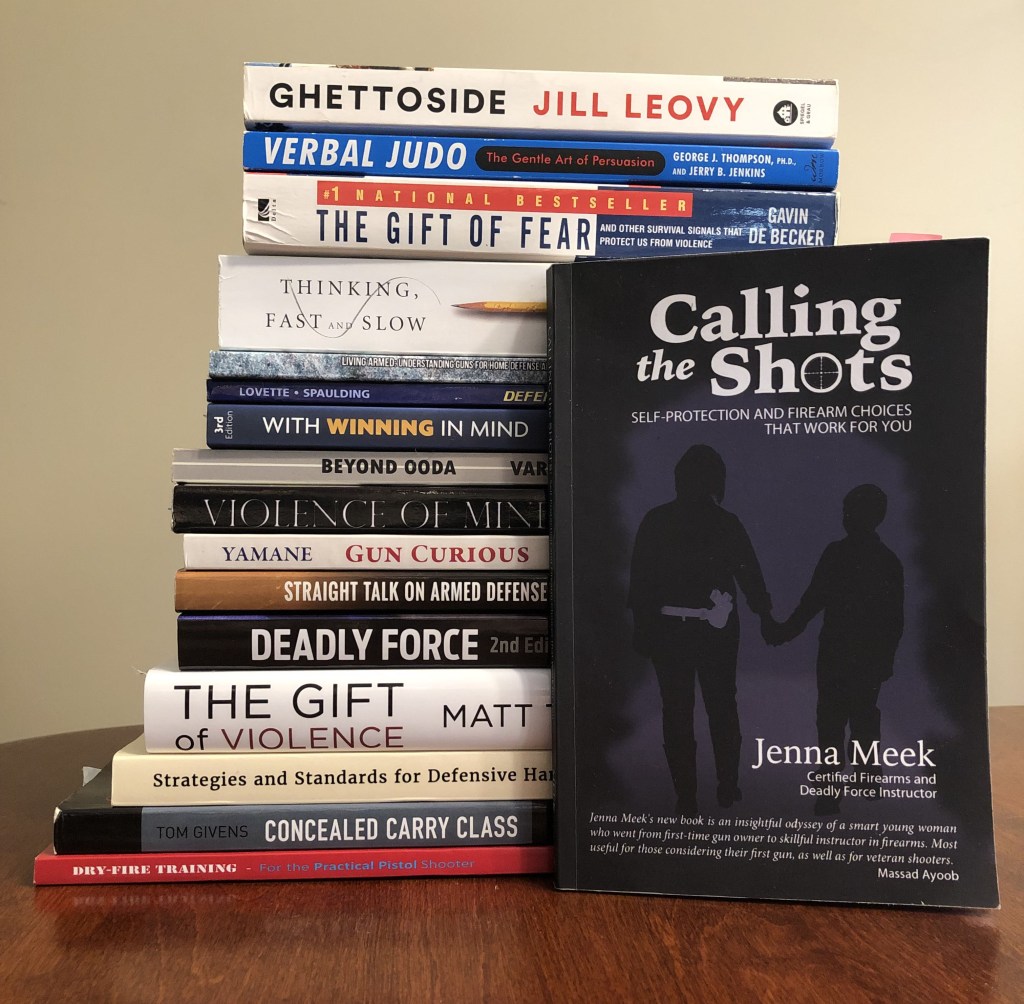

Welcome, friends. As the title suggests, today I’ll be reviewing Calling the Shots: Self-Protection And Firearm Choices That Work For You by Jenna Meek.

As I recall, I first heard about this book on Greg Ellifritz’s Active Response Training blog. While I can’t remember the exact post, I suspect it was either Greg’s own brief review of the book or his recommended reading list, on which it also appears.

This text was of immediate interest to me given my vision for Introduction to The Armed Lifestyle: that is, an inclusive (and I mean that in a matter-of-fact rather than pandering way) publication that reflects the ongoing cultural shift towards Gun Culture 2.0 and the concurrent changing demographics of gun ownership. For reference, during the pandemic:

“An estimated 2.9% of U.S. adults (7.5 million) became new gun owners from 1 January 2019 to 26 April 2021…Approximately half of all new gun owners were female…20% were Black…, and 20% were Hispanic.” (emphasis mine)

“Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results From the 2021 National Firearms Survey” by Miller et al. Annals of Internal Medicine.

In other words, not only is self-defense most gun purchasers’ primary motivator, but an increasing number of those individuals are also women and minorities. Arguably, though, race and sexuality don’t factor into most of the logistical and practical decisions about what firearms to carry and what equipment to use to do so. Not as much as sex does, anyway.

As if it weren’t bad enough that women are the most frequent victims of violent crime, anatomy and clothing limitations also interfere with their ability to carry tools for self-protection. Without belt loops on skirts, dresses, and certain pants, most belt-mounted holsters are off the table. Even something as easy to pick up and run with as POM OC spray with a pocket clip is harder to keep on-body because so many women’s pants lack pockets.

Possibly the biggest pitfall for the fairer sex to avoid is the avalanche of flashily marketed garbage products ostensibly catering towards women. These subpar and sometimes dangerous offerings include pink stun guns, cheap bedazzled pepper spray, chintzy ring knives, and a gaggle of frighteningly unsafe, frilly lace ‘holsters.’

Clearly, women have to wade through a lot of bullshido and snake-oil-hawking to get to what works. As a man who’s never had to do so, I approached Calling the Shots hoping to learn from someone who’d found those answers for themselves.

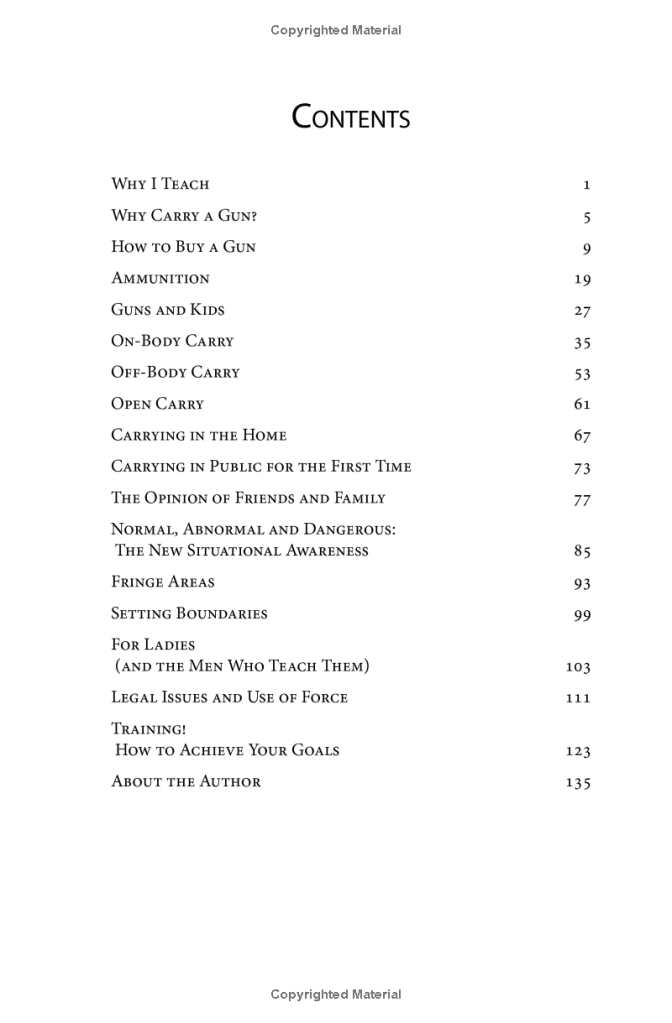

Synopsis

Jenna begins by relating the “miserable” experience of shooting her husband Jeff’s new pistol, remembering its unwieldiness, unpleasantly loud report, and the harshness of its recoil. Undeterred, she shrugged off the negativity of this initial outing and resolved to re-engage the task of learning how to shoot on her own terms. Jenna describes how her journey unfolded from there: she went on to buy a first pistol of her own choosing, attend her first class (where she discovered that that pistol may not have been the best choice after all), and eventually purchase a second gun based on what she’d learned.

After this introduction, Jenna fills the remainder of the book addressing the why, how, where, and when of carrying a handgun. She also touches upon the critically important adjacent topics of situational awareness, use of force laws, and how to begin pursuing formal training.

The Good

Overall, I would say the book’s three strongest attributes are its breadth, accessibility, and presentation, all three of which work together to make it as effective and attractive as it is. If these sound like abstractions, bear with me—I promise you, they are not.

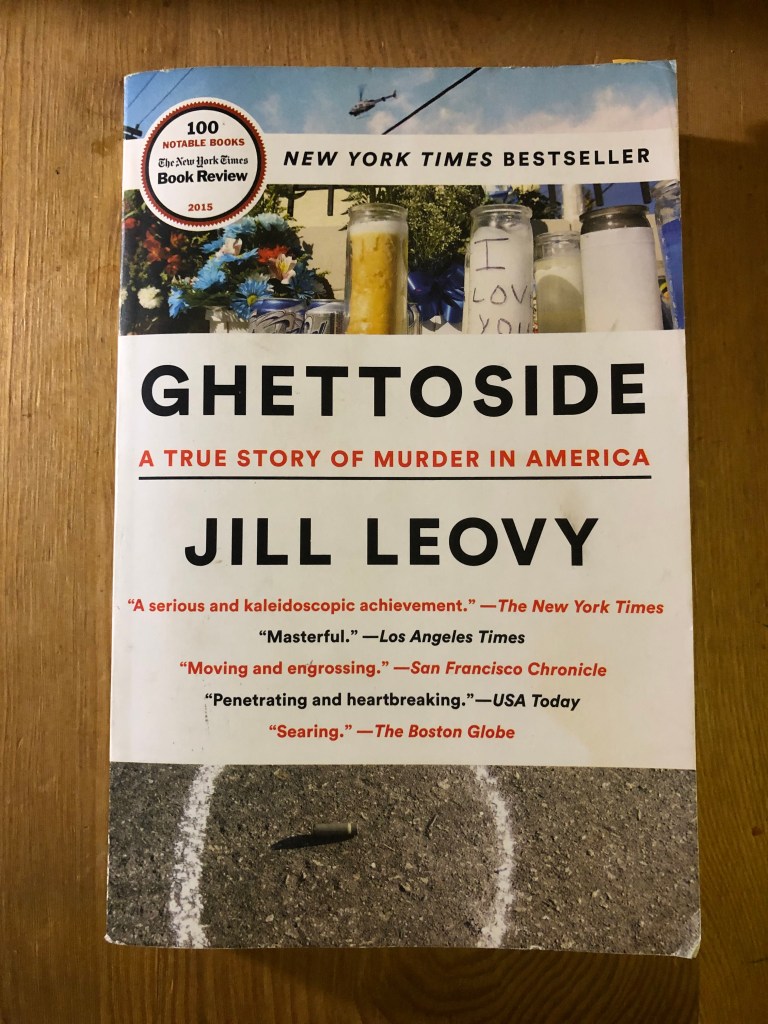

Wide > Deep

There are a number of critically important concepts, topics, and potential risks competent armed self-defenders should be aware of. Calling The Shots introduces readers to nearly all of them without becoming overwhelming. Not only that, but it does so more succinctly and efficiently than longer books like Tom Givens’ Concealed Carry Class while covering some gaps that the latter doesn’t address.

In fact, it speaks to considerations that go basically unaccounted for in any other print book I’ve read thus far: what Alex Sansone terms, in his tagline, “the overlooked social aspects of the armed lifestyle.” Several authors point out that broadcasting our training, tools, and knowledge on social media and among casual acquaintances could get us targeted for violence or theft. But relatively few have commentary on how it can pose the milder but still consequential problem of social friction.

Here’s a passage from Jenna that I referenced in the post on self-knowledge:

“I have a diverse network of friends… Within this group is a person who thinks it is appropriate behavior to call attention to the fact that I might have a concealed weapon. This started happening shortly after this person found out what I do for a living. It started off as him asking me if I was ‘packing.’ The first time this happened it really caught me off guard and I kind of laughed it off and walked away. I really didn’t think it was any of his business or anyone else’s business if I had a gun on me. So I just swept it under the rug. However, that was the wrong way to handle this situation because it escalated from there. Sometime later this person decided that it would be a good idea to pat me down when I walked into a room. I was so taken aback by this that I froze.” (83)

I would argue that bringing the possibility of interactions like this to readers’ attention is a far better use of page space than a chapter on flashlight techniques.

That brings me to another endorsement of Calling The Shots: it contains zero fluff, and certainly doesn’t include any information at the expense of anything more relevant (case in point: I think Concealed Carry Class would have been much better served by chapters on home carry and child safety than on drawing from the holster and reloading a double-action revolver).

Another particularly strong section of Calling The Shots is its overview of the gun selection process, which is probably the most to-the-point treatment of the topic I’ve yet seen in print. Jenna manages to hit all the key ideas in less than ten pages: consideration of intended use, readiness to compromise, and understanding of the fine balance between concealability and shootability. She employs the relatable analogy of the car-buying process to illustrate the relationship between pistol size and body/hand size. She also gives helpful tips like making a list of pros and cons for each handgun you’re considering, creating a short list of possible contenders, and then renting some or all of them to shoot before you buy.

Overall, by taking an approach that is more pithy than comprehensive, Calling The Shots succeeds at accomplishing a lot with very little book.

Accessibility

When I say the book is accessible I’m referring to its…

- Tone. Jenna’s tone is, for me, the most appealing aspect of her writing. Her narrative voice is friendly, relatable, and down-to-earth. She makes excellent use of analogies and personal anecdotes to illustrate her points. Her sense of humor also contributes a lot to the personality of her prose, making it feel more engaging and conversational.

- Length and form factor. Approachability matters. At first, length might seem to be the simple end result of the composition process. In other words, one might assume that a book is as long or as short as it is simply because that’s when the author decided to stop writing. In some cases that may be true. But, in Jenna’s case, I suspect brevity was her intention, and she executed upon it well.

Trim size and thickness might also seem superficial; however, I think they matter quite a bit. Just as we want to make a range trip sound inviting and fun to our gun-curious friends, I think that ideally the best way to package information for new consumers is to err on the side of convenience. Even to someone who’s not averse to chipping away at longer books, a thick tome is undeniably more daunting. I also suspect there’s something about a petite 5.25×8” trim that some people find more appealing than a taller, wider 8.5×11”. The potential consequences of a cookbook or literary soap opera going unread may be negligible. But if a woman is interested in self-defense enough to consider reading a book, I think that the less there is to dissuade them from doing so, the better. - Diction. You will not find words like ‘myelination,’ ‘proprioception,’ or ‘kinesthetic’ in Calling The Shots. While these wouldn’t be out of place in any writing about armed self-defense, they would likely be a speedbump for the uninitiated. In this respect, it is very user-friendly.

Something About Books and Covers

I admit that, of the three qualities I initially highlighted, presentation is the least critical overall. But, given how rough-around-the-edges some other publications in the discipline are, I think it’s worth mentioning.

Overall, the typesetting and interior formatting are very good. Tiny revolver wingdings are even used in place of traditional bullet points, which I actually think is quite cute. The photographs have good resolution. When juxtaposed with the charts and figures in Strategies and Standards for Defensive Handgun Training (2023) by Karl Rehn and John Daub, the difference is night and day.

Make no mistake: Strategies and Standards is at least a four-star read chock-full of high-quality information priceless for students and instructors alike—from some extremely studied, credible people, mind you. But the resolution issues do detract from the overall professionalism of the publication, in my opinion.

The Not-So-Good

I believe it’s a testament to its quality that the few things about Calling The Shots I take issue with are not overarching weaknesses of the content, writing style, or large portions of the book, but rather what amounts to a list of nitpicks. Personally, I think that’s decent proof of overall success.

However, there are a few things that would make me reluctant to hand this book off to a female friend without any follow up for discussions and caveats.

- The first headscratcher appears right on the cover under the author’s name: “Certified Firearms Instructor and Deadly Force Instructor.” Now, perhaps this was a marketing decision: a choice to present some level of credibility up front and boost shelf appeal while keeping the cover copy unspecific and ‘low level’ to avoid turning off novice readers with unfamiliar acronyms or organization names. If that was the case, I would empathize. After all, as Karl and John discuss in Strategies and Standards most gun owners—and certainly most prospective gun buyers—have no knowledge of available instructor certifications and credentials or what they mean, anyway.

Puzzlingly, though, Jenna never goes into any detail about what certifications she’s referring to, nor does she name any of the instructors she’s trained with in the past even at points where it seemed opportune to do so.

Based on the content of the book itself, I suspect the undisclosed credential is an NRA or USCCA instructor cert. Don’t get the wrong idea: those are accomplishments to be proud of, and I certainly think they’re worth mentioning to set oneself apart from the great unwashed. They may not be as ‘prestigious’ as an Advanced Rangemaster Instructor certification, but so what? It could be argued they’re sufficient for teaching totally unexperienced, first-time or entry level shooters. In any case, to readers like myself who have no certifications, almost anything would lend more credibility than the absence of any details whatsoever.

Whether a certification was granted by this organization or that one isn’t really the point; it’s the principle of the matter. A vague résumé or CV is one of the universally recognized red flags in a potential instructor.

“5 Firearms instructor red flags” by Caleb Giddings, GAT Daily

It may not be as egregious as an ex-military ‘instructor’ who claims their unit affiliation and combat experience is classified top secret, but it is questionable. - Jenna makes the valid point that “you can protect yourself far better with a .22LR that you can hit your target with than the .45ACP that you are not able to shoot accurately or quickly. I can almost guarantee that if you needed to pull a weapon in the name of self-defense that your attacker won’t stop and ask ‘Hey, what is that you’re shooting?’” (25)

This is a great point that dogmatic caliber debaters would do well to heed. While terminal ballistics mean that shot placement is only one determinant of an anatomically significant hit, hitting in the first place is kind of a prerequisite for incapacitation.

“Is .22LR Viable for Self Defense? Exploring the Controversy” by Uncle Zo

Unfortunately, she then goes on to say, “More likely, they will run out of fear of your ability to neutralize the threat they bring.” It is generally accepted that many, if not most, defensive gun uses do end that way. But I would personally be a little bit more cautious of invoking the certainty implied by “will” when “may” might be more appropriate.

Unsurprisingly, criminals tend to be involved in a lot of gunplay. Mr. John Hearne says in his Crime & Criminals: Risks and Mitigations lecture that some 36% of felons in one FBI study reported having been shot before. It’s also very common for them to have had guns pointed at them in the past.

While the most recent data I’ve been able to find to corroborate this is three decades old, you can pretty much take anything John says to the bank. I’ll see about reaching out to him to get a citation for that 36% number.

Basically, there’s reason to believe the presence of a gun might not scare an attacker away.

- Another statement I take great issue with is made during her discussion of printing: “if a person with a concealed weapon does figure out that I am armed I don’t much care, as we’re on the same team, as it were” (74–75). Pardon my French, but that is a big, dangerous fucking assumption.

‘Printing,’ as you may or may not know, is a term that refers to an instance in which the shape of a concealed pistol becomes noticeable through the fabric of a shirt, jacket, or other garment.

An armed individual is not by default a good, sane, sober, moral, prudent individual. Felons carry weapons themselves, and—since the consequences they might face for failing to hide them effectively are just as steep as ours might be—many are likely just as adept at spotting a concealed pistol as self-defenders are.

Not only are there risks to being ‘made’ by a criminal, but also by ostensibly nonhostile parties like your peers, professors, coworkers, supervisors, or strangers in public. If you don’t believe me, just ask Alex.

- On the whole, her treatment of holsters is not the worst but could be much better both in terms of the advice itself and her articulation of it.

There is certainly something to be said for informing newcomers about all of their prospective options, including the bad ones; however, it is vital that a distinction be made between acceptable and unacceptable after all the choices have been laid out for the end user. This is where Calling the Shots could stand to be more explicit.

For example, Jenna mentions “holsters [that] have ‘buttons,’ for lack of a better word, that you have to press in order to draw your gun” (36–37). Most will quickly recognize this as a passing reference to the Blackhawk Serpa and holsters of a similar design. She puts it mildly when she opines that “these are not the best holsters out there,” citing the design’s conduciveness to negligent discharges (37). I don’t think it would be amiss to take a stronger stance, given the stakes.

“The Serpa Compendium” by Greg Ellifritiz, Active Response Training blog

Here are a few other bones I have to pick with her coverage of the topic:- Jenna recommends the use of the so-called ‘tip test’ to test holster retention (36). This seems to be one step shy of the shake test that PHLster has debunked. To be very clear, every quality holster should do the bare minimum of retaining a pistol when turned upside-down, but suggesting that that alone is enough to consider a holster safe is a bit dubious.

- While Meek correctly states, “if the trigger guard is not covered then it’s not a safe holster,” I would have liked to see her go on to specify that ‘covered’ means more than a layer of fabric or stretchy nylon (36). It’s a little worrying that she presents carry methods like lacy ankle and thigh holsters, compression tops, and belly bands without the caveat of ‘these are not safe unless used with a dummy-corded Kydex trigger guard.’ A DAO revolver might be the exception, but even then, there’s still the matter of retention to consider.

- Even though Meek does not recommend nylon holsters for EDC, she says, “One thing I really like to recommend the nylon holster for is to try out a new carry method now and then. This way you know if something will work out for you before you spend the time, energy[,] and resources on a long[-]term holster” (42). This doesn’t make much sense to me. If a holster isn’t safe for EDC, how is it safe to try out?

Moreover, I don’t think a person considering a transition from 3 o’clock to AIWB, for example, would learn much of anything from ‘trying out’ the latter position with a $5 Uncle Mike’s with a money clip belt attachment. It would be like using a rental suit to try and get a feel for an Armani. You simply wouldn’t have a comparable experience to a purpose-built appendix holster with DCC clips, a wing, wedge, and position-specific belt like a Tenicor Zero or EDC Belt Co Foundations. A much better solution would be to borrow quality equipment from a friend or mentor, if possible. - Jenna offers the following as a tip:

“… I should mention that not all EDC holsters are good for using on the range or in a class. If the holster is collapsible or you are physically unable to reholster your weapon one handed, it is likely not going to be allowed by most reputable instructors. This can be a safety issue…If you do have different holsters for use at the range and for EDC, then I absolutely recommend practicing with both of them so you can become proficient with all of your gear” (52).

To me, this seems to imply that, somehow, a holster deemed too dangerous to allow on the firing line can still be perfectly safe to carry a loaded firearm in public. I don’t quite see how that adds up. This could possibly be said to be true of more specialized carry methods like shoulder holsters or Flashbang bra holsters, which—while safe when used by experienced shooters—may not be allowed by an instructor if they don’t know the person who intends to bring it to their class. However, it’s not clear whether or not these are what she had in mind.

- I fully appreciate the impediments women’s clothing poses to on-body carry. Really. And I think anyone who has carried a gun IWB understands the attractiveness of off-body carry—especially women, many of whom already carry purses. Off-body carry like purse carry can be safe and viable, even if it is a suboptimal method (especially given the advent of the PHLster Enigma, which was released several years after the publication of the book). However, the author’s well-meaning cautions about the risks have the unintended consequence of making a strong argument against it. If an assailant tries to rob you of your concealment purse, she says, let them take it rather than resisting and being killed for it: “Do not risk your life to save your gun. I know it sounds counter-intuitive for many, but let it go and just get the heck out of dodge” (59).

On some level, I see where she’s coming from. If a purse-snatcher grabs the bag off your shoulder in one slick motion and runs off into the night, would chasing him down really be the most prudent course of action? Even though arming a criminal is not something we take lightly, I cede to her that pursuit would be ill-advised.

The quote begs the question, though: what if you can’t “just get the heck out of dodge”? In this case, her recommendation is a lot like ‘just stand up if the fight goes to the ground.’ Okay…but what if your purse-snatcher is not just a property criminal but a violent criminal actor, who, after being given your purse, moves you to a second location to rape and murder you? You’ve forfeited your best means to stage a counter counter-ambush and break contact. - After the high center chest, Jenna writes, “Our second point of aim should be the pelvis or pelvic girdle. This is a highly effective target. There are major arteries here and a person will not be physically able to advance on you if this area has been shattered. Besides that, if you ever need to point a gun on that region of a male attacker, he will likely think twice before continuing to attack you, out of sheer terror of having a weapon pointed at this region” (115). Although that last sentence is meant in what I fervently hope is a joking manner, it comes far too close to the ‘racking the shotgun to scare the home invader away’ line of thinking for my taste.

- I think it’s a bit disingenuous to say that “there are only a few moving parts [in a revolver]” (15) and that “there are more moving parts…[in] a semi-automatic pistol than a revolver” (16). Looks can be deceiving.

- Following the pattern precedented above, she follows reasonable advice with a sketchy claim, writing, “…you should only pull out your gun if you intend to use it, but if the act of getting your gun out deters the attack and you don’t have to use it, then you are better off. It is easy to explain to law enforcement at that point why you are standing there with a gun” (120, emphasis mine). I admire her optimism, but…I have my doubts about the ‘ease’ of such an ‘explanation’ to police, to say the least. I think a self-defender with a drawn pistol should more likely expect to find themselves in a very stressful game of Simon Says, if not be ventilated outright by responding officers.

- “One of the first things you should also do is decide what type of training you are looking for. Do you want to become a competition shooter, or learn how to use a gun as a self-defense tool? Maybe you want to learn military tactics and learn how to clear houses of zombies. Or maybe you just want to learn how to be safe and effective with your weapon of choice so that you can shoot as a hobby. This is a very personal and individual thing; there is no right or wrong answer here. Different schools will have different specialties[—]ours happens to be civilian self-defense using a firearm” (125).

Her point that different instructors and schools specialize in different things is well taken. The irony of this statement is that, immediately after saying that there is no right or wrong answer, she states explicitly what is, in fact, the right answer.

Is there anything wrong with tactical fantasy band camp? Of course not. But, in the words of Tamara Keel, “if you find yourself stacked up on a doorway like an ersatz SWAT team with a bunch of complete strangers, ask yourself what of value you are actually learning (especially if the only qualification you know for sure that they have to be standing there in the stack with you is that their check cleared).”

The Verdict

While to some it may seem like I’m grasping at complimentary straws by putting somewhat greater emphasis on how, rather than what, was written, that is truly the level of importance I place on economy of language. This is partly because I find it so hard to be concise myself.

You’ll likely notice that one common theme of my criticisms is my contention with perceived oversimplification, over-certainty, and insufficient detail. In fairness, if Jenna were to add information to provide what I believe would be the proper level of nuance on some of the book’s topics, it would be working against the very brevity I’m applauding her for.

In conclusion, while I think the book was well written and contains decent information overall, I would hesitate to loan or gift Calling the Shots to a woman in my life unless I knew they were already connected with a mentor able clarify and correct certain assertions it makes. If, however, you’re acquainted with a female, rookie self-defender who you are sure is going to learn far beyond the level of information it presents in their own education and training, this could be a good starting place.

Personally, my next move will be to check out Kathy Jackson’s book The Cornered Cat: A Woman’s Guide to Concealed Carry.

Thanks for reading!