Welcome, friends.

Human beings have a few underlying directives that I believe feed into our decision to prepare for self-defense.

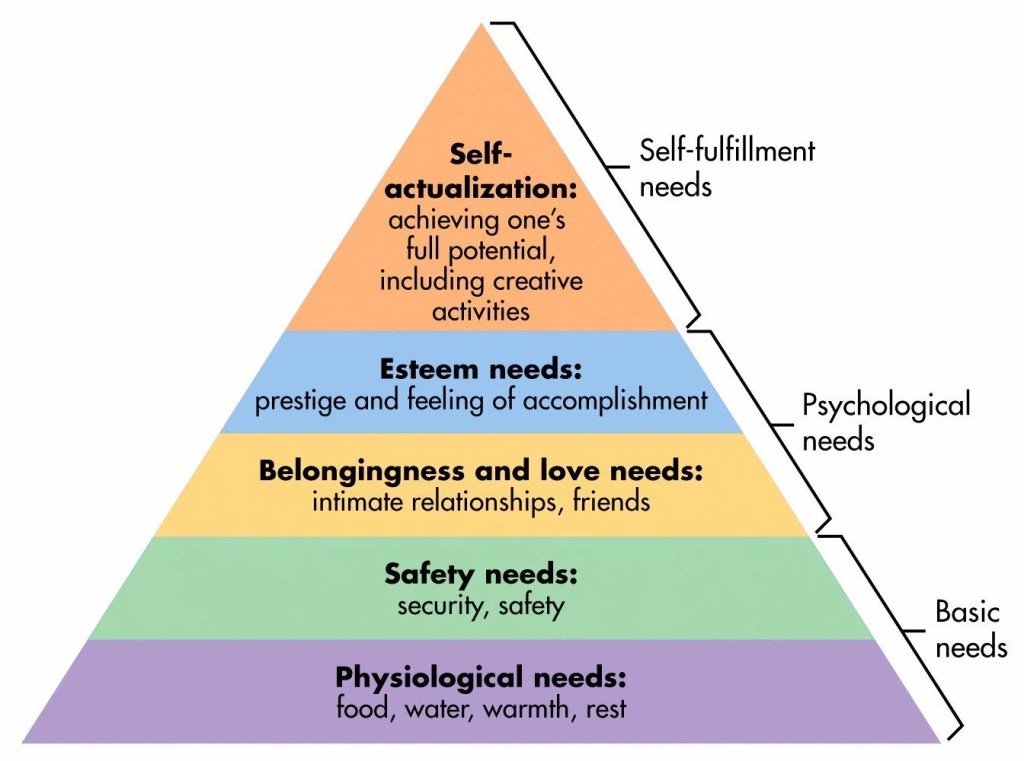

First, we want to stay alive, in the most literal sense: to be a conscious, sentient human being drawing breath on this planet. Our genetically programmed biological imperative is to keep living because that’s the bare minimum required to pass on our DNA or to do anything else. Luckily, most of us rarely have to worry about short-term survival, so we tend to focus on meeting higher-level needs (if you’re familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy, this would be moving towards the top of his pyramid).

Second: we not only want to have a life, but as much as possible, we want that life to be good. I hope everyone can put their finger on at least one thing—ideally several things—in their life that currently brings them joy and fulfillment. Even if it’s as simple as a beautiful sunrise, a tasty meal, or a good book, there are moments of happiness and positive experiences even on bad days. We want to keep that.

Third and finally, we want to either achieve a better quality of life or maintain our current quality of life. While we try to enjoy the aforementioned positives to the degree that we can in the ‘here’ and ‘now,’ most people are also working towards something more or better in the future. Maybe you want to start a business, get married, go to med school, travel the world, get that raise or promotion, compete in the Olympics, buy a house, or write the next great American novel. Maybe your goal is just to continue collecting paychecks or to keep a roof over your head, food in your kids’ mouths, and clothes on their backs. Those are also perfectly valid. Whatever the case, we want to continue pursuing those goals and avoid any setbacks, if possible.

We recognize that getting shot by a carjacker or armed robber, beaten by some rowdy drunks on the sidewalk because you ‘looked at them funny,’ or cracked upside the head by a road rager with a baseball bat is going to stop us from doing those three things. So, we buy a gun and train with it. We start training a martial art and hit the gym. We carry OC spray and a handheld white light.

And I believe those are good decisions. Violence does happen, and it would definitely stop you, if not from living altogether, then from having a good life and from most of your pursuits towards bettering it. If you’re lucky, maybe only temporarily. But quite possibly forever.

What I would submit to you, then, is this. If you’re committed to becoming a responsible, competent self-defender through training and practice, you shouldn’t undermine your efforts by neglecting to prepare for more likely contingencies. Unexpected expenses like a surprise medical bill, car trouble, or loss of income can have a serious negative impact on your quality of life if you don’t have safeguards in place. They’re also likely to put any plans to improve your life on hold. Don’t do yourself a disservice by overlooking the less-exciting risks just because they aren’t as fun to prepare for.

Philosophy

A basic understanding of personal finance dovetails with the basis of the Armed Lifestyle as I’m currently trying to lay it out in my writing: a practical, wholistic outlook on self-defense, realistic preparation, and a healthy defense-life balance.

- Practical. Practicality in this context means, “actionable under real circumstances and feasible for people with real constraints on time, money, and energy.” It is what’s possible and makes sense for the average civilian with limited support and resources.

- Wholistic. The best approach to preparedness will be multidisciplinary, incorporating hard and soft skills (defensive gun use, martial arts, verbal judo, edged weapons, medical), legal knowledge, physical and mental health (strength and cardio, diet and nutrition, sleep, spiritual fitness), and a personal ethos of goodness, sanity, sobriety, morality, and prudence.

- Realistic. Realism involves an honest appraisal of the most likely risks to you and your stakeholders and entails having your priorities straight. If you believe you have a greater chance of getting into a gunfight on the way home than being get laid off, I would hazard a guess that that’s probably not true, and urge you to reconsider (if for some reason that is actually true, please move, if possible, or go with a long gun and body armor and friends who also have long guns and body armor). It makes sense to invest in your training and practice, for sure! But personally, it makes much more sense to me to have six months of living expenses in reserve than 10,000 rounds of rifle ammo. Pistol ammo might be a little more excusable in comparison, but I digress. It’s safe to say that if you’re not paying the rent or mortgage, preparation probably shouldn’t be your priority.

- Defense-life balance. Preparation for self-defense is a means to an end, not an end in and of itself. You should prepare to defend your life, but not at the expense of living it. Go out, meet people, visit beautiful places, make memories! The ideal outcome is to train and practice until we reach a degree of competence that instills genuine confidence in our ability to handle whatever life throws at us. That way, we can enjoy life without being keyed up and paranoid all the time. Now, wealth doesn’t necessarily guarantee a happy, fulfilling life, but financial security and wellbeing are significant quality of life indicators. If nothing else, they give peace of mind and give you more time for family and friends, relaxation, travel, and whatever else brings you joy.

Please note that these principles aren’t mine in any way, shape, or form. This philosophy is just a synthesis of what I’ve managed to take in through osmosis over the past few years and distill out of the collective knowledge and reflections of dozens of people who are all much smarter and more experienced than I am. It’s a brainchild with so many parents that I can’t begin to give proper accreditation. I do, however, want to mention Mickey Schuch, Alex Sansone (in general, but especially for the YouTube video embedded below), and Melody Lauer (specifically for this Facebook post) for their prominent influence.

One very critical point I want to make is that you shouldn’t mentally restrict the concept of ‘making good financial decisions’ to things like opening a high-yield savings account, maxing out your Roth IRA contributions, or optimizing your credit cards to make the most of perks and cash back. Yes, all of those things obviously qualify. But the unsatisfying truth is that mundane stuff like getting enough sleep and brushing and flossing twice daily are also extremely important in this context—especially in the long run. The positive relationship between sleep deprivation and all-causes mortality is no joke. Neither are the costs of dentistry and oral surgery (just ask Dr. Sherman House). Just because those things don’t directly involve your checkbook and bank accounts doesn’t mean they aren’t financial decisions in and of themselves.

With that in mind, here are some suggestions on how to think about money, equip yourself, and pursue training and practice as a frugal self-defender.

My Two Cents

If you have unlimited money to spend on guns, ammo, and classes, more power to ya—but this isn’t for you.

Put things in perspective. If you’re not making rent/mortgage or car payments but you’re larping with NODS, maybe reevaluate your priorities. That’s obviously an egregious example. More generally, I think this comes into play when weighing decisions about equipment and training. For example, I’d argue civilians are better served by pistol courses than rifle courses, and probably better served by a CPR/AED class than a TCCC class. On an even more basic level, I think it makes more sense for most people to spend on a gym membership, a treadmill, or some free weights before they spend on a gun.

Prioritize skills over equipment and practice over training. Acquiring new skills does require an initial investment for instruction, at which point the largest upfront costs are usually out of the way, and you can practice what you’ve learned. But buying stuff won’t make you more betterer. Likewise, taking class after class won’t help you unless you reflect on and think critically about what you’ve learned before applying it during practice. I recently took my first class with Tim Herron, who commented at one point that taking any more than two two-day classes per year really makes it difficult to fully absorb and implement what you’re learning. And, in any case, I think that a single two-day class annually and consistent, year-long dry fire with live fire validation at the range will be just about as much as most people can swing financially.

Recognize you have fewer ‘needs’ than you think. There are some things you will need like electronic ear protection and quality eyewear, plus a good holster. Otherwise, ammo and a stock gun with maybe some aftermarket iron sights will go a long way. Beyond that, SMEs like Ben Stoeger and Annette Evans agree that one of the soundest investments for both dry- and live-fire training is a purpose-built shot timer, and I concur.

I’ll go into a little bit more detail about PPE and holsters now before we continue. In the spirit of maintaining quality of life, it really behooves us to protect our hearing and vision, because money cannot bring those back. Again, this is not to disparage individuals who are blind or deaf or any degree of either, but it’s nice to be able to see and hear, and I personally would like to continue doing both. And, if I had to guess, I’d say hearing aids and reconstructive eyeball surgery are expensive, so if those are costs we can avoid, we should do so.

The same applies to holsters. There are probably plenty of self-inflicted GSW victims who could give you a tally of every penny that a flaccid nylon Uncle Mike’s or shoddy Serpa (plus broken safety rules and often poor technique) cost them. Not only will a crappy holster put you at risk in training and practice, but it could easily sabotage you in the unfortunate event that you’re ever forced to use a pistol defensively and cost you your life. Which, again, defeats the purpose of carrying a gun in the first place. Plus, a quality holster will only run you between $50–$100, so a person can’t really even make the argument that they’re saving a lot by cheaping out on a We The People holster or an Amazon special.

This may seem like much ado about nothing, but there’s one final point about holsters from my book I want to reiterate here. Now, it’s generally accepted that drawing from concealment is a more advanced skill than drawing from an outside the waistband (OWB) holster. But here’s my take on it. I think that, for most people, it makes the most sense to find a passable EDC setup—meaning a holster and belt suitable for use in the real world—and train with that. You could always buy a cheaper OWB holster dedicated exclusively for training, and I do think that could make learning the pure shooting aspect of things easier. But, if I were to go that route, I would want a duty-grade holster with active retention like a Safariland, which would run you from $150–200 or more.

Buy once, cry once. This saves you time and money, which in this context are both important. When you purchase subpar equipment that either breaks or wears out and then inevitably replace it, you incur a higher net cost than you would have if you’d bought the better-quality replacement right out of the gate. Not to mention, you’ll have to spend time working to recoup that money (or wait to accrue interest on savings or investments)—which, again, is time we don’t get back.

You also save yourself time by not having to carry out unnecessary repairs, troubleshoot, and generally try and polish turds. Unreliable guns are the worst, because you’re forced to spend that much more time and ammo vetting them to see if they can really be trusted with your life. That’s time that could be better spent in the proverbial pursuit of happiness or making more money. Finally, if you’re distracted by constant gun or gear issues during a class, then you’re pissing away money that you paid up front; instead of spending that time learning, you’re preoccupied by peripheral crap that’s diverting your attention from the main objective.

Just about every class I’ve ever taken has had some kind of disclaimer saying something to that effect.

Buy a 9mm. This is one of the only recommendations that I will make for equipment, and it’s one that I feel quite strongly about. While the availability of mainstream calibers has not been a given historically due to consumer-driven shortages and supply chain issues, I believe that 9mm is the only viable chambering for defensive pistols from a purely economic standpoint. For reference, as I write these words, a case of 9mm Magtech is $259. A case of .380 ACP is $339. A case of .40 S&W is $349. A case of Blazer Brass .45 ACP is $439. Even if 9mm is in greater demand and would therefore be affected more by a potential shortage, that price difference is impossible to overlook.

Make wise decisions when shopping online. In 2023, it’s likely that you will purchase most if not all of your equipment—including firearms—online. The internet is a godsend in terms of convenience, for sure, but obviously not without its risks to security. If you accidentally wire your life savings to a Nigerian prince, you’ve seriously impaired your ability to fulfill your Mission. If you get ripped off, you’ll be obligated to spend a lot of time on the phone with the bank or credit card company trying to get your hard-earned doubloons back. And, after all that, there’s still a chance that they’re gone forever.

Do dry fire practice. Honestly, the ability to practice without the cost of ammunition isn’t even the primary reason dry fire is constantly hyped by serious shooters. But focusing on how great it is for skill building can make you temporarily forget the astronomical amount of money it saves you. It allows us to cut out the drive to and from the range—the gas, the wear and tear on your car, and the commuting time—plus the time spent gathering and packing guns, ammo, and gear beforehand. The ability to press a trigger without flinching every time from the distracting thought that you’re converting money into noise is a huge benefit.

Invest in self-defense insurance. Criminal defense attorneys, paralegals, expert witnesses, and private investigators don’t work cheap. Interaction with the legal system is inevitably a mental, emotional, social gauntlet: your mere involvement is cruel enough punishment without the monumental price tag. In Straight Talk on Armed Defense, Marty Hayes writes that that price tag will be, “at least $100,000…and perhaps much more.” Personally, I’m not so optimistic. If you think it makes sense for you, do your due diligence, compare different providers, and pray you never have to use your benefits. Ryan Cleckner wrote a great comparison article for Recoil magazine that you should check out if you’re interested.

Take it seriously. My last and final point comes full-circle: take the journey seriously and embark upon it with full knowledge of the stakes and risks. Know the laws governing the various tools of the trade and the use of deadly force. Educate yourself, prepare mentally, and make peace with your mortality and whatever you believe comes after. Remember that there is more than one way to fail your Mission. Death, paralysis, or grievous injury and chronic pain are Mission failures. Selling your home to fund a legal defense after a critical incident is a Mission failure.

Other Resources

Jacob Paulsen wrote an excellent article on this same topic over at ConcealedCarry.com that very much deserves your attention. He goes into much greater detail and gives some sound advice about where to spend and how to save.

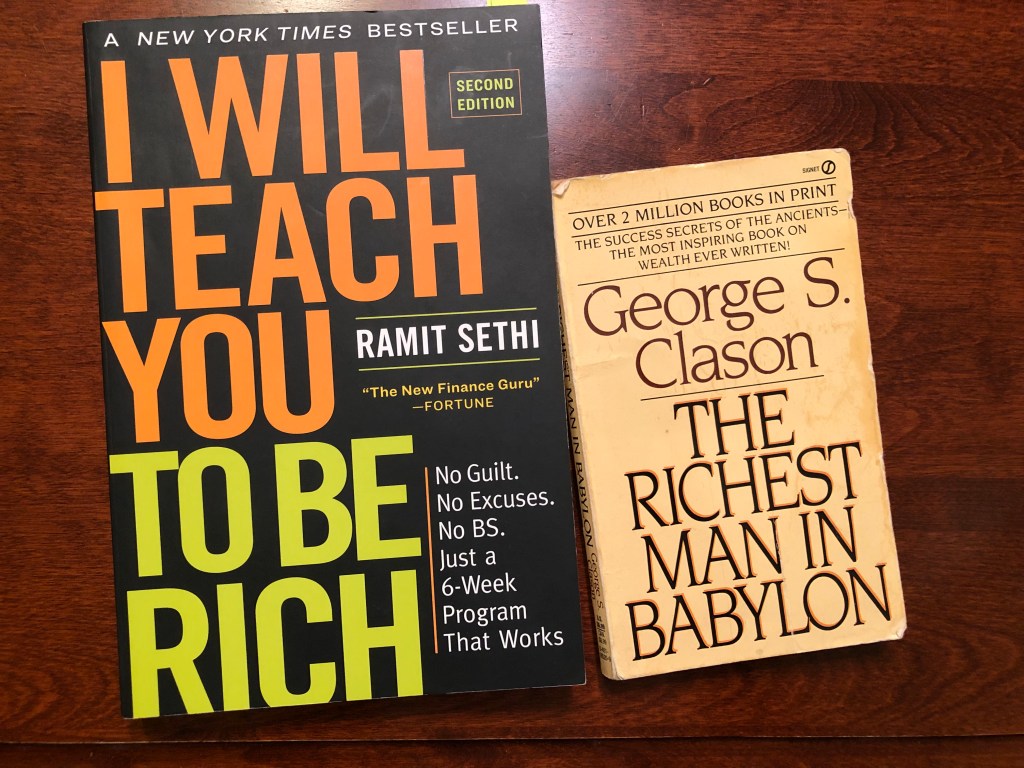

I also have two bonus book recommendations for you.

The first is I Will Teach You to Be Rich by Ramit Sethi. I cannot praise it highly enough. It’s funny, well-written, and chock-full of great advice. Plus, it’s a well-laid-out and handsomely printed book.

The second is The Richest Man in Babylon by Samuel Clason. Don’t be fooled by its age—they call classics timeless for a reason. I wish someone would have given it to me to read earlier in life.

Okay, I lied. One more. If you have elementary-school-age kids, buy them a copy of Lunch Money by Andrew Clements. It’s a great little story about the value of hard work, entrepreneurship, and creativity. I mention this one only because I distinctly remember how I felt reading it when I was younger and was kind of reminded of it when I read The Richest Man in Babylon for the first time.

Thanks for reading!

I know this got a tad long, so thank you for bearing with me. Right now, I’m working on a blog post about a popular dry fire aid that I’ve had a fair amount of experience with, so stay tuned!