Welcome, friends.

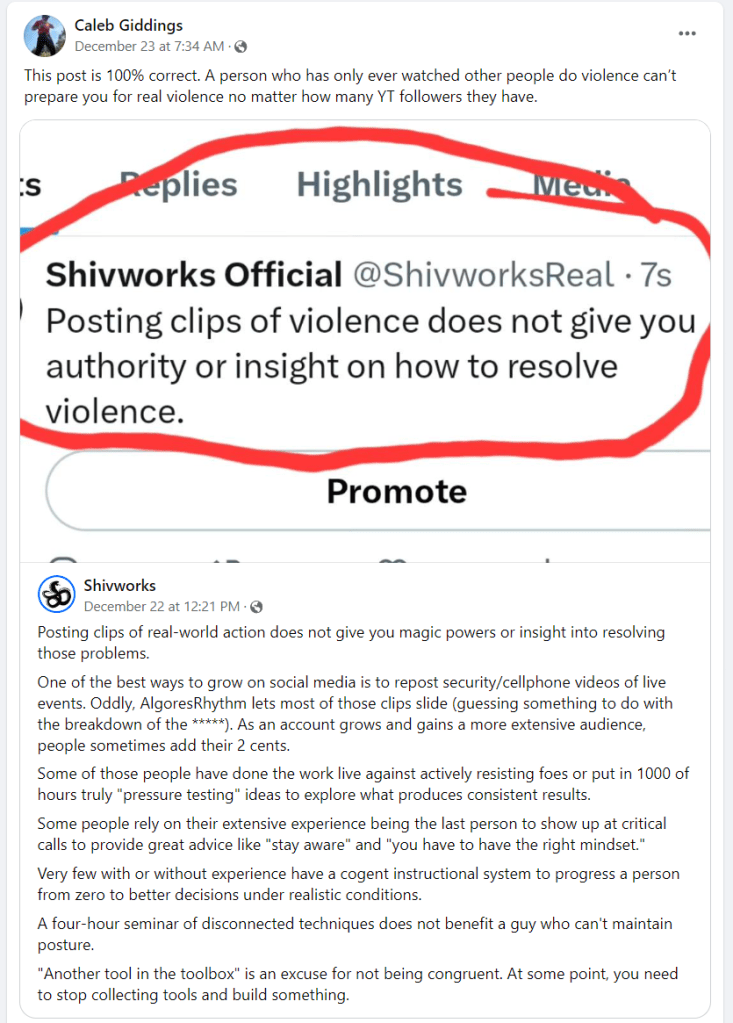

The exigence for this blog entry was a social media post from the Shivworks group and its subsequent reposting by revolver expert Caleb Giddings. It was posted to Facebook and Instagram on December 23rd (it appears to be a screenshot from Twitter, so I assume it was posted there as well, but can’t confirm that since I personally don’t have an account).

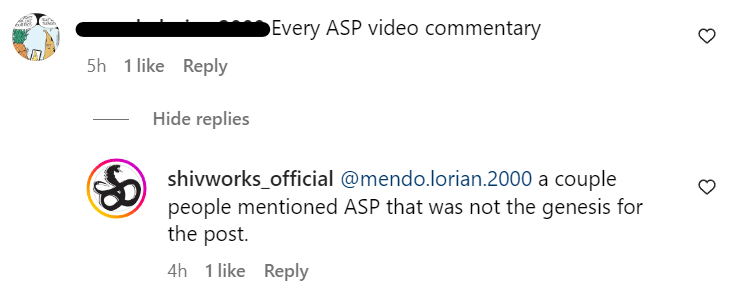

Several commenters on both platforms directly and indirectly snubbed YouTuber John Correia, creator and host of Active Self Protection. Shivworks clarified in a reply to one commenter that the post was not directed at John, but that hasn’t stopped people from reaching their own conclusions.

Reading this discourse has left me feeling a bit stuck, conflicted, and confused. From my perspective, neither party’s credibility is in question: I have tremendous respect and admiration for both the Shivworks cadre and Caleb. I have not yet had the chance to train with Craig Douglas but do plan to attend ECQC when it comes to my neck of the woods in 2024, as one of my mentors Derreck Almasi has said it will. I likewise very much value the opinion of Mr. Giddings as a very high-level competitor, skilled shooter, and accomplished instructor (not to mention as a prolific author and accomplished professional in the firearms industry, as I can only dream to someday be).

At the same time, I put considerable stock in John’s training résumé, instructor certs, and expert witness experience. It’s been my long-held belief that the content Active Self Protection puts out is absolutely priceless for self-defenders. Was I wrong? When individuals you look up to disagree with one another, what and who do you believe?

This whole dialogue has prompted a few questions that I feel should be explored: what is best practice for the use of spectated violence as a learning tool in self-defense preparations, if it has a role at all? On a broader level, what qualifies someone to comment on and prepare others for violence?

We may not be able to definitively answer those questions in this blog post, but I think we can begin to unpack them at the very least, and touch upon some adjacent issues that can be discussed in the future. Let’s dive in.

Who is John Correia?

If you’re not familiar with Active Self Protection, I highly recommend you subscribe to the channel in spite of the naysayers (I’ll endeavor to have explained my rationale for this by the end of the post). I would opt not to click the bell icon, though, because uploads are frequent and the volume of corresponding notifications can get excessive.

With more than three million subscribers and over one and a half billion aggregate video views, ASP—with its backronym abbreviation denoting attitude, skills, and plan—is home to some 3,400 defensive encounters caught on camera. The footage in question is internationally sourced and submitted. Incidents are captured on CCTV cameras, bystanders’ smartphones, video doorbells, dash cams, and badge cams, in the case of officer-involved shootings. The recordings depict everything from road rage, barfights, home invasions, carjackings, strong-arm robberies, and workplace violence to cold-blooded murder.

This far from the gruesome voyeurism it may first seem to be. Unlike gory LiveLeak compilations, Active Self Protection has more to offer than shock value. Rather than just recycling the raw content or giving his first impressions in ‘reaction’-style videos, John presents narrated breakdowns of the events portrayed and provides thoughtful commentary based on principles he has derived from analyzing the outcomes of countless other incidents. His opinions are presented reasonably and without appreciable political bias. The only real possible point of contention is whether his additions are substantive and whether or not his recommendations should be acted upon.

We can deduce from his CV that he is, if nothing else, a prolific student and quite an accomplished shooter. I confess, I don’t know how rigorous the requirements for testimony as an expert witness are. I want to say it counts for something, but don’t know enough to say one way or the other.

Now that we’ve gotten that brief introduction out of the way, let’s talk about the content itself.

Andragogy of Video

I think it makes sense to start the main discussion by reviewing what John himself has said about the use and limitations of Active Self Protection videos. I’ll primarily be citing these two videos from his behind-the-scenes channel Active Self Protection Extra.

In “The Pedagogy of Video,” he states up front that ASP content should be considered education, not training. Whereas training and practice seek to increase the participant’s skill, education exists to increase their knowledge. Already, this would seem to indicate John is not claiming to prepare anyone to defend themselves from violence with his videos alone.

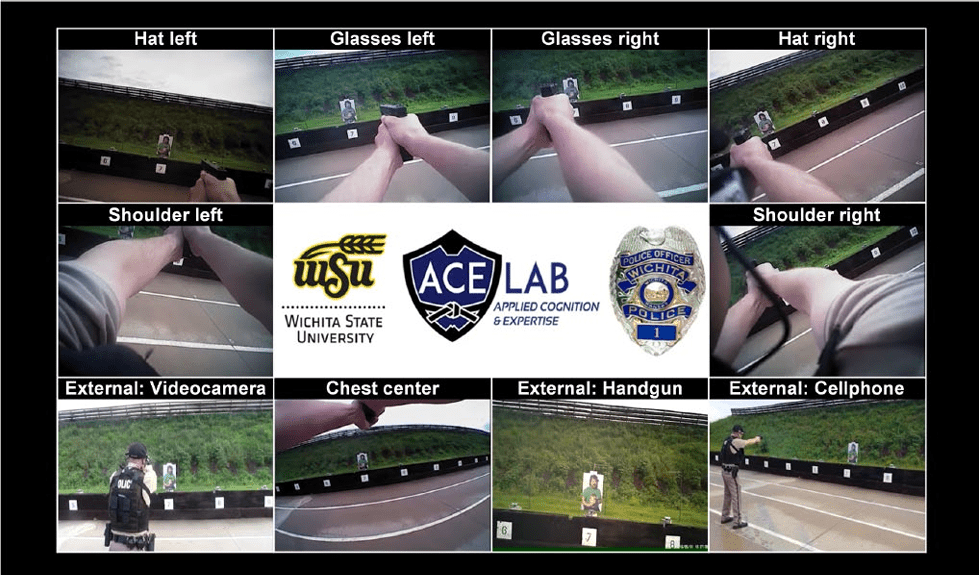

He goes on to identify several inherent limitations of video footage that should be kept in mind by viewers. First, many videos only provide a single point of view, although some show the same event from multiple perspectives. Additionally, these points of view can fundamentally never reflect what was seen through the eyes of the victim or intended victim. Elevated, fixed security cameras will almost always show more than would be directly observable to a person at ground level; moreover, any fixed camera may not capture all the action, should it move out of frame. Even in the case of the glasses-arm-mounted or epaulette-mounted body-worn cameras (BWCs) sometimes worn by law enforcement, which arguably come closest to a ‘true’ first person, an eye-level view does not necessarily equate to a 1:1 representation of what the wearer would have seen.

One reason for this is that, as one of John’s PowerPoint slides reads in “The Use And Limitations Of Video Analysis In Self-Defense,” video doesn’t “take foveal vision into account.” I know a bit of anatomy, but I had to look that up. As I now understand it, the fovea is the eyeball part responsible for high-focus central vision for tasks like reading—almost like the opposite of peripheral vision. Basically, whereas cameras record everything in equal clarity (or lack of clarity, depending on the resolution) we can only see a portion of our total FOV in focus at one time.

There are a few other considerations:

- Some cameras use wide-angle lenses, which can distort distance and depth. The bullet point on the slide in video 2 reads, “Perspective skewing from fisheye lens.”

From watching YouTube clips of people racking up massive dental bills on skateboards, I vaguely recalled a fisheye lens being a different thing. Sure enough, a commenter on that video actually shared some illuminating info on the topic (right). - Poor resolution can obscure details. The parties involved may have seen something that influenced their decision making in the moment that is not visible to us on video.

- Because of camera angles, critical elements of a given incident may not be captured in the limited field of view. For example, while an attacker may be visible, we might not be able to see whether the backstop is safe.

- Badge cams often have an audio buffer and will not record verbal commands, threats, gunfire, or anything else until they are activated manually or wirelessly. The length of that buffer may vary depending on hardware or software, but usually there is a 30-second stretch of silent video before the audio cuts in.

Finally, a given video may not portray the events that led up to or precipitated an incident in their entirety, or at all. This is unfortunate because avoidance and deescalation are of such interest to us. It may be because those events transpired at a different location, happened some time before the main conflict, or were simply not recorded and can only be recounted by witnesses (whose reliability can be questionable). Sometimes, the confrontation may have been brewing for months or years before escalating to violence, like in this case of two feuding neighbors. Obviously, no video can provide that level of context. In those scenarios, John relies on news stories to fill in the gaps of what we don’t know.

So, at the end of the day, it’s not quite possible to say “what a video shows is what happened” unless you follow that statement with a big asterisk.

Nonetheless, I think that this type of content has a lot of value to offer. Even videos in which law enforcement personnel are the focal point can still be helpful to civilian self-defenders, so long as we keep in mind the differences between our Mission and theirs. I’ll write more on that another time, but the main difference is that our goal is to break contact with our attacker(s), whereas LEOs are usually initiating contact and doing so with a disparity of force on their side.

With all that being said, let’s move on to the pros of viewership as I perceive them.

Spectated violence is particularly beneficial as a strong reminder of the existence of evil and the necessity of self-rescue. It’s one thing to read a headline or hear a news anchor report that such-and-such a tragedy befell John or Jane Doe on a certain street in a particular city. But it is much harder to distance oneself from an incident witnessed personally, even if only via a recording. On video, the semi-pixelated silhouettes of the victims and attackers become more recognizable as human beings like ourselves; the grainy parking lot backdrops appear more familiar. Life ends before our very eyes. Innocents spend their final moments watching their bodies drain of blood as bystanders look on dumbly. Villains go out in a blaze of glory. Some defenders triumph while others perish.

We can use these incidents to facilitate mini visualization exercises. By mentally inserting themselves into a given scenario, a viewer can begin to build rudimentary mental maps, make pre-decisions, and set appropriate boundaries.

According to John, another benefit is that allegedly the brain has a difficult time differentiating between a real experience and a virtual one. He cites flight simulators and some VR games as examples. He also mentions horror movies, which some people do have sympathetic physiological responses to. Honestly, I’m not sure I buy the notion that watching a video on your phone could be nearly as immersive as a VR headset. But I haven’t yet looked into the matter to see how much water this claim holds.

In the past, I have seen some other personalities in the self-defense space insinuate that John is encouraging viewers to mimic the actions of the individuals in videos who successfully defend themselves. I don’t believe that’s the case. Long-time viewers of the channel will point out that it is not unprecedented to see untrained and ill-equipped (or totally unarmed) citizens triumph in the face of violence. Furthermore, it is typical that even successful outcomes are still tainted, to varying degrees, with mistakes that we should note and avoid. Our training and practice should be oriented towards what will achieve an optimal outcome, and that is rarely what those videos depict.

There’s a quote from an excellent article by Phil Elmore that directly applies here: “just because it worked doesn’t mean it works… and just because it didn’t work doesn’t mean it doesn’t work.” In short, because mortal conflict is so dynamic and unpredictable, recommendations for a technique, tactic, tool, martial art, etc. shouldn’t be made based on a one-off victory or defeat, and those that are shouldn’t be heeded.

Accordingly, the recommendations for tactics and mindset made by John and Mike are founded in principles distilled out of the several thousand encounters covered on the channel thus far. Since I’ve read scientific articles for work where the sample size was only n=50 or even less, I thought (and still think) this was a healthy body of work to draw conclusions from. But then, I recalled seeing a Facebook post Caleb had written on an unrelated topic, in which he said, “the plural of anecdote isn’t data.” That really puzzled me, because I had thought the exact opposite.

Immediately, I did some Google-fu and found some people talking about that expression. It turns out that what the man who coined the aphorism really said was, “the plural of anecdote is data.”

To be very clear, I’m not trying to say “ACKCHUALLY, you said the quote wrong,” or put words in Caleb’s mouth. In the context of that Facebook post, I understood his intended meaning to be more like not all anecdotes are created equal, which is a valid point. For example, just because a certain defensive cartridge does well in a Paul Harrell meat-shooting demo and also performs well in a Lucky Gunner ballistic gel test does not mean that those two things are equally valid as evidence.

This blogger says that he will continue to use the misquoted version of the expression—that the plural of anecdote isn’t data—because anecdotes can be subject to reporting bias. To that point, it’s worth noting that Active Self Protection videos are not curated to include only videos in which the ‘good guys’ win. He doesn’t cherry pick incidents to cover so far as I’m aware.

Detractors might also argue, in the spirit of the original Shivworks post, that the lessons John presents are perhaps not unfounded but are basic and cliche like the given examples of “be aware” and “have the right mindset.” After all, how qualified does one really need to be to give advice like “lock your doors” and “close distance before attempting a gun disarm”? Maybe not very. But I think it would be a mistake to write off this advice as ‘goes without saying.’ Sometimes we need a catalyst to prompt some self-reflection and perform an audit of our own capabilities and attitudes.

Even if John was not the originator of the underlying concepts behind the given advice, I would argue there is something to be said for introducing relevant ideas to the mainstream of the internet and getting people to actually practice what you preach. If you read the comment section (which, to be fair, is rarely advisable) it’s clear that ASP is accomplishing that.

Take for example this comment I gathered for a project during my two-semester stint in grad school.

It appeared on a 2021 ASP video entitled, “Las Vegas ‘Security Guard’ Takes Out Three Guys.” The commenter is referencing an earlier video from the channel (viewer discretion advised—it’s not for the faint of heart).

I’ve seen many other comments from viewers saying that they apply the lessons from John’s content to help keep themselves safe. To me, this constitutes proof that the videos are doing tangible good in the real world.

The question, remains, though: can anyone who has never spilled blood in violence prepare others to do so, or even speak on the topic with any credibility? Phrased differently…

My Shooting Instructor Has Never Shot Anyone. Does That Matter?

The funniest response to this question I’ve ever seen was given by a gentleman on Facebook, whose name I can’t recall: “yes, depending on how many times they tried.”

In all seriousness, though, it is a question that comes up with some regularity and that there doesn’t seem to be a clear consensus on. Even Varg Freeborn, who acknowledges that “instructors who have the entire package [of teaching ability, skills, and firsthand experience with violence] are extremely rare,” ultimately doesn’t say how highly that particular attribute should rank in the hierarchy of qualifications.

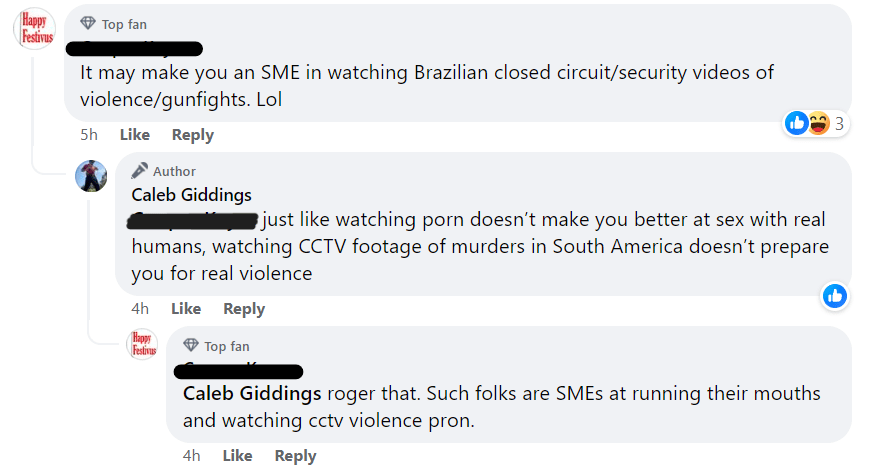

Opinions abound, however, about what doesn’t qualify someone to teach self-defense. Take for instance one of the screenshotted comments above, where Caleb writes, “just like watching porn doesn’t make you better at sex with real humans, watching CCTV footage of murders in South America doesn’t prepare you for real violence[.]”

This is almost a paraphrase of the virgins-describing-sex analogy used by Dave Grossman to describe the uninitiated and unqualified discussing violence. It’s also quoted by Craig Douglas in his chapter of Straight Talk on Armed Defense. Even though Grossman’s work has been subject to more than a little criticism, the saying is not without some merit.

The difference is that virgins want to lose their virginity.

In this analogy, popping your cherry means possible death, disfigurement, impairment, plus a trip through the legal gauntlet of the criminal justice system, potential incarceration, financial ruin, and lasting psychological changes.

At the end of the day, we cannot—and should not want to be—involved in real experiences. This is one of the few nits I have to pick with Varg Freeborn’s writing as a whole. Yes, to someone who has never bloodied their hands in self-defense and braved the legal and psychological aftermath, any discussion of violence is purely theoretical. Force-on-force scenarios and ECQC evolutions are the closest we can get to the real thing but are, of course, mere substitutes. If that leaves us less prepared in relation to someone who has ‘been there and done that,’ so be it.

Someone from the proverbial other side of the tracks undoubtedly has a ton to teach the rest of us squares about the real-world application of violence. But I don’t believe that a lack of firsthand experience should disqualify an instructor—especially when the ideal outcome we’re seeking as defensive practitioners is to avoid firsthand experience.

I admit, there is a difference between an instructor who claims their training will unequivocally make you capable of defending yourself, period, versus someone who only claims to teach skills that will help you defend yourself. But I would argue that that’s largely a matter of semantics.

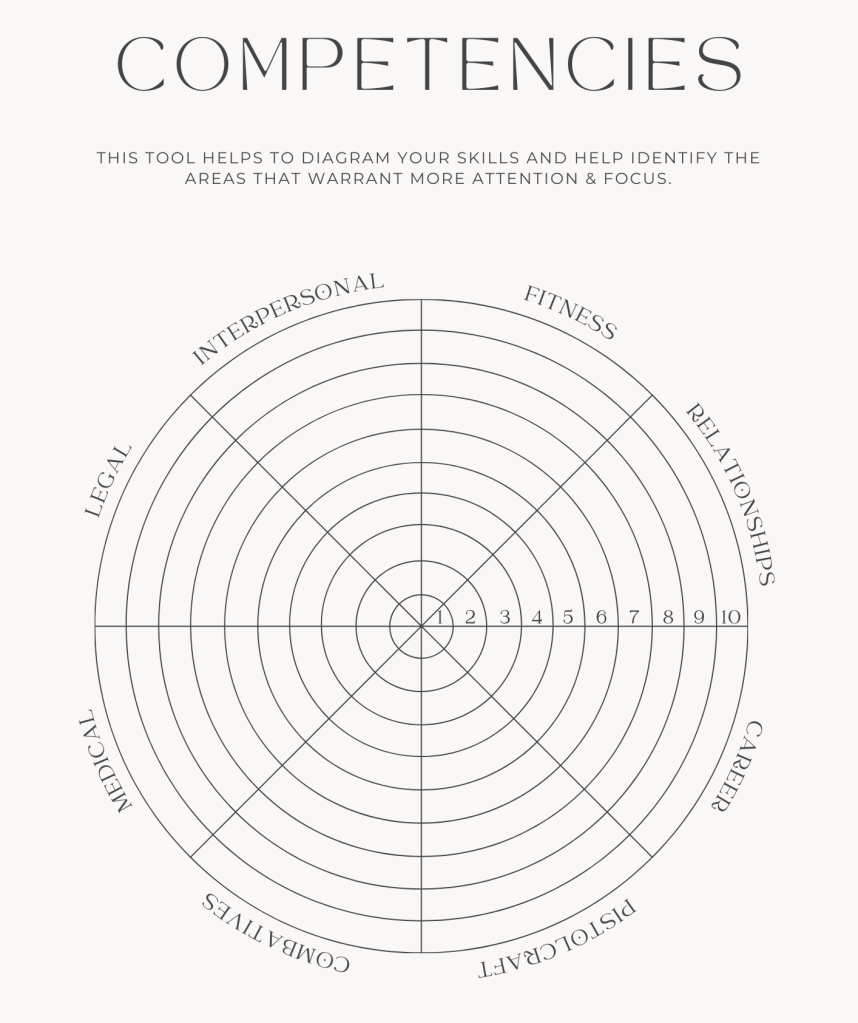

While a teacher does bear responsibility for marketing themselves “as the complete package” without being qualified to address more than a single piece of the puzzle, I believe the onus is on the student to approach training realistically. That is, they have to recognize that even a multi-module class like FPF Training’s 2-day Street Encounter Skills and Tactics cannot fully prepare them to counter interpersonal violence. If a given class covers only the shooting component of the equation, it’s the student’s responsibility to see it for what it is. Each area of study is just one spoke in the wheel, and taking a single class is only dipping your toe in the water.

Basically, it depends on what you mean by prepare. For example, Craig might say “a four-hour seminar” won’t prepare you to defend yourself, and I agree with the use of the word in that sense. However, I would disagree with any assertion that a BJJ black belt or competitive shooter couldn’t prepare you for violence because their backgrounds are in sports, and not strictly in self-defense. Again, semantics.

Skills approached with self-defense in mind are best learned when presented in that context, but ultimately, where and how those skills are applied falls to the end user.

All told, I value a prospective instructor’s teaching skills and capability to be an effective educator above all else. Relevant, highly developed skills are a very close second. Deep appreciation of the stakes and consequences of real violence—the kind that can only come from lived experience—is valuable, but not common, and ultimately not indispensable.

Here are some final thoughts:

- Not all “real violence” is equally relevant to us.

- We can’t readily gain the sort of experience “real violence” affords, nor should we want to.

- An instructor’s experiences are not transferable.

- An instructor with too much of this type of experience should be eyed critically, since so much of our Mission is to avoid getting any experience of the sort.

- Violent encounters are so unique that two people may take away completely different lessons from their respective incidents.

Other Resources

Here are some videos and articles I referenced while writing this post:

Research on Body-Worn Cameras and Law Enforcement (from the National Institute of Justice)

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/research-body-worn-cameras-and-law-enforcement#0-0

I also drew heavily on Varg’s books Violence of Mind and Beyond OODA.

Thanks for reading!

At the end of day, I guess what we learned is that people love to throw shade at one another, as the kids say. I, for one, will continue to listen to and value the opinions of Caleb, Craig, and John.

Thanks for bearing with me through this one. I’ll probably be revisiting it periodically to see if it still makes sense.