Welcome, friends.

Today, we’re going to be discussing pepper spray, or OC spray, in industry lingo.

I originally planned to incorporate a big chunk of the content that follows into an upcoming post on the gimmicky self-defense products that are marketed to women, but decided it would be better suited for its own dedicated blog post.

OC Spray is both a must-have tool in any armed self-defender’s kit and perhaps the best solution out there for self-defenders that aren’t willing, legally able, or of age to buy and carry lethal means. It’s intuitive, inexpensive, and low on the continuum of force. Plus, it’s physically low-profile, and multiple methods for on-body carry can make it easier and more comfortable to keep close at hand than a pistol or sheathed knife carried IWB.

Much of the following information has been synthesized from the below-linked articles by Greg Ellifritz and Chuck Haggard, the frequently asked questions page on SABRE’s website, and this glossary from the Mace website. I referenced a few other sources, and I’ve tried to indicate those where and when they come up.

“Pepper Spray- How to Choose it and How to Use it” by Greg Ellifritz, Active Response Training blog

“How to Pepper Spray” by Chuck Haggard, CONCEALMENT Issue 10

As Greg alludes to in his introduction, impartial info on the science and chemistry that factor into selecting and using pepper spray is hard to come by, since so much of it is put out by the makers of the product themselves. As industry-leading brands, I trust SABRE and Mace with respect to general knowledge on the topic and trust myself to see through the marketing copy when needed. Similar to the field of terminal ballistics, in which much of the research is conducted or sponsored by manufacturers of ammunition, critical thinking is necessary.

Why OC?

Pepper spray is a short-ranged, less-than-lethal distance tool: an aerosolized chemical irritant meant to temporarily impair an attacker’s eyesight and upper respiratory system.

It has a number of advantages over other defensive tools. For example, it:

- Is legal for adults to own, carry, and use for self-defense in all 50 states (outside of NPEs, and with some state-level restrictions on capacity and strength).* This makes it exceptionally easy to travel across state lines with.

- Can be checked in a bag without being declared like a firearm when flying.

- Is low-cost at around $20 or less.

- Can be carried in hand unobtrusively, without spooking lookers-on or upsetting the constabulary. This allows a self-defender to stage it for fast deployment if trouble seems imminent.

- May not violate weapons policies on college campuses. For example, Duquesne’s weapons policy specifically excepts “legal chemical dispensing devices that are sold commercially for personal protection.” The weapons policy at my alma mater SRU doesn’t mention pepper spray at all—only weapons “capable of inflicting serious bodily injury.”

* I’m still not a lawyer.

Between Tongue-Fu and Kung-Fu (and Well Short of Gun-Fu)

As good, sane, sober, moral, prudent self-defenders, any force we use must be proportional to whatever unlawful force is being actively directed at us or that we reasonably believe is imminent.

This principle of proportionality means that, if a person was charged by a knife-wielding maniac, resorting to lethal force by drawing down on him and shooting until he broke off the attack or dropped would probably not be excessive. If a person was jumped in a rowdy bar and hands were being thrown, using a commensurate amount of physical force to defend themselves would probably be a justifiable response. I use the word ‘probably’ because these are simple hypotheticals. There are infinitely more variables in play in real-world situations, all of which have a bearing on what may or may not be legally reasonable.

Basically, if you’re attacked with deadly force, you can respond in kind. If you’re attacked with physical force, you’re well-situated to use an equivalent amount in self-defense. This is a gross oversimplification, of course—it’s always best to use the least amount of force necessary—but bear with me.

In Pennsylvania, Title 18 of the Criminal Code only defines the former; all force that doesn’t meet that definition gets lumped together as ordinary, non-deadly force—that is, any not likely to cause death or serious bodily injury. As such, OC spray is a form of physical force, in practice. Why does that matter?

Chuck Haggard gave an insightful explanation on episode 86 of CCW Safe’s In Self Defense podcast.

It’s not just that it’s easier to justify using physical force than it is to justify using deadly force. It’s also that it’s so much easier to reasonably claim you feared assault than it is to claim that you feared for your life. In other words, the bar is lower for explaining what you did and what caused you to do what you did. This is especially true if you have working knowledge of the MUC process and pre-assault cues or indicators.

Accordingly, if the worst were to happen and we ended up spraying an innocent party, the legal consequences wouldn’t be nearly as severe as they would had a bystander had been struck by gunfire. It’s likely, Chuck says, that we “would be prosecuted for a misdemeanor simple battery because [pepper spray] would be considered the same level of force as if you punched him in the nose.”

Spicy Eye Poke

Thankfully, we don’t have to wait until we’ve been punched in the face to use physical force to defend ourselves.

Because it is, after all, a ranged tool, and to avoid cross-contamination, pepper spray is probably best used when a person reasonably believes physical conflict is imminent but before distance is closed. For example, if a self-defender is managing an unknown contact who is exhibiting aggressive body language, manifesting intent to do harm, and not responding to requests or commands to honor spatial boundaries, they may consider deploying spray.

For this reason, Craig Douglas has referred to OC as a canned version of the eye jab technique he and Brian teach in ECQC and EWO. Just like the actual, manual eye jab, pepper spray is a less-injurious preemptive strike that may preclude the need to use a higher level of force later on by nipping a situation in the bud. Furthermore, deploying OC doesn’t require any athleticism and has the potential to work regardless of extreme disparity in size and strength. This is one big advantage it has over martial arts. And, again, the most obvious benefit is that a self-defender can bless a deserving subject with hot sauce from beyond arm’s length.

As such, although it technically occupies the same step on the force continuum as empty-handed skills, OC spray is a distinct option with unique capabilities, and so is not redundant even for self-defenders that grapple, wrestle, or strike. For the elderly or disabled, it may be the only less-than-lethal option available to them besides verbal judo.

Personally, I would be more inclined to consider OC spray my first resort and use empty-handed skills as a backup or alternative. While serious injuries from OC exposure aren’t unprecedented, they seem to be exceedingly rare. In comparison, we know that a single punch can kill, and a shove leading to a fall could cause a TBI; furthermore, most joint lock submissions (if you recall from my first ever blog post about BJJ) would likely be considered serious bodily injury by a prosecutor or jury. As for chokes…Well, just ask Daniel Penny how that can go wrong. I’d rather not risk it.

While it is a common concern, the general consensus is that it’s not likely a person who carries pepper spray as a complement to lethal tools will be legally penalized for not using it first should they have to resort to deadly force. A prosecutor can always try to twist the facts to suggest a defendant was trigger happy, but using pepper spray before a gun is not a legal imposition the way duty to retreat is in states where it exists.

An attacker threatening death or serious bodily injury will have effectively ruled out milder, less forceful responses by using a higher level of force at the outset. Given the distances likely to be involved and the negligible time available to transition from less-than-lethal to lethal, using the former when the latter is called for would be a mistake—one that, luckily, the law doesn’t require us to make.

Blinded by Science

Now, let’s get into the technical stuff.

The Secret Formuler

Pepper spray products on the commercial market are generally made up of three ingredients:

- Oleoresin capsicum (OC): This oil is extracted from the placenta of chili peppers from the genus Capsicum and is the active ingredient of most pepper sprays. It is fat-soluble and, in practice, absorbed via direct contact with the skin and eyes, inhalation, or ingestion. It irritates the mucus membranes of the nose and throat, which can cause a choking sensation, cough, and snot production, in unscientific terms.

- Chloroacetophenone (CN): originally the active ingredient in Mace™ and one of the chemicals in older forms of tear gas, CN causes blurred vision and burning of the eyes, nose, throat, and skin. According to the SABRE FAQ and the CDC, it’s been largely replaced by CS for crowd control use by military/LE and in and pepper spray formulations.

- Chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile (CS): abbreviated for obvious reasons, this is a lacrimator that causes skin irritation, a burning sensation in the throat, and tear production. It’s the main component of modern tear gas.

OC-only compounds are the most common, but companies like SABRE and Mace sell blended formulas that also contain CS.

Both brands also sell sprays that incorporate a UV marking dye for suspect ID post-use, although the cynic in me feels like that’s putting an awful lot of faith in the justice system. Personally, I wouldn’t hold my breath waiting for the police to track down a would-be mugger when literal murders go unsolved.

There are three relevant specs when it comes to pepper spray:

OC concentration

Typically expressed as a percentage between 1–20%, this number represents what portion of the mixture is OC. According to Greg, it “determines how long the effects will last, with the higher concentrations yielding effects over a longer time period.”

Scoville Heat Units (SHUs)

The Scoville scale is a subjective measure of chili peppers’ heat levels. Named after American pharmacologist Wilbur Scoville, who created the scale in 1912 during research for a pharmaceutical company, the scale is primarily used by foodies jonesing for the socially acceptable masochism of hot food. It’s still sometimes used in advertising for pepper spray, though.

Per the Dept. of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology, here’s how SHUs are measured:

“[The process] involves extracting the capsaicinoids from a pepper and diluting them with a solution of sugar and water until the heat of the pepper can no longer be tasted by a panel of professionally trained taste testers. More dilutions indicate a higher heat index rating and therefore a higher concentration of capsaicinoids. The test relies on the initial amount extracted from the pepper as well as the training of the taste testers.”

It was innovative for its time, but it’s clearly not the most scientific method.

Because SHU measurements are inherently subjective, most OC spray brands note that they test the potency of their products using a technology called high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). You science nerds will have to look into that for yourselves to learn more, because I’d be out of my depth trying to explain.

Major Capsaicinoid Content (MCC)

Capsaicinoids are alkaloids, or nitrogen-based organic compounds, that occur naturally in pepper plants and give them their pungency or perceived hotness. There are either three or five main capsaicinoids, depending on who you ask. Mace only names three—Capsaicin, Dihydrocapsaicin, and Nordihydrocapsaicin—but SABRE mentions five.

It is the content of these so-called major capsaicinoids that determines the strength of pepper spray, not the overall OC concentration or SHUs. Still, you may see all three measures being used together. For example, you might see a spray advertised as being 10% OC with 1.40% MCC and 2.2 million SHU (POM’s specs, in case you were wondering).

SABRE’s spray clocks in at 1.33%; Mace only specifies 10% OC concentration but not MCC. SABRE’s Frontiersman bear spray tops out at 2%.

The majority of sources agree that MCC is the best measure of potency.

“Look for a product with a MCC content of at least 0.7 to 0.8,” Chuck advises. “…A good top end is the common ‘police strength’ 1.33% MCC.”

Both Greg and Chuck are clear: know what you’re buying. If the specs aren’t advertised, there’s a good chance they’re underwhelming.

Stream, Gel, Fog and Mist, and Foam Patterns

Because it offers a bit more range, more precision, and less chance of blowback, I’m inclined to recommend stream-pattern sprays. Fog or mist sprays have their own advantages and different tactical uses, but “are most affected by the wind, and most prone to cross-contamination of bystanders, or yourself if you spray into the wind.”

Regarding gel and foam sprays, Chuck writes:

“Gel sprays have a pattern much like a streamer, but are thicker and have as near to zero aerosolization as one can get in an OC spray. Respiratory effects are basically zero, so a hit to the bad guy’s eyes is a must for any useful effect. In my observation, both from being sprayed and from use on students in scenario training, the gels are noticeably slower to take effect versus cone- and stream-type sprays.”

Wasp and Dog Spray

Any trustworthy source will tell you that wasp spray is not a self-defense product. Unfortunately, viral posts similar to the one below still make the rounds on Facebook, like this decade’s evil reincarnation of chain emails. The suggestion is to buy a can to use for self-defense.

If you need any dissuasion, read this news story, this one, this article by Lars Smith writing for GAT Daily, and this post by Kevin Creighton at his AmmoMan.com School of Guns blog. See also Annette’s Facebook post on the topic below. In the comprehensive post that I’ve been citing thus far, Greg states in no uncertain terms that, “Wasp and Hornet Spray is not an acceptable substitute for OC.”

Sure, being hit in the eyes with any kind of pressurized liquid is probably disorienting. But that’s about all that could be said for it.

Yes, it does shoot farther than a pocket unit of pepper spray (although not a comparably sized MK3 or MK6 unit), but that 20-foot range simply isn’t needed. If you can avoid an unknown contact, do so. If they’ve come to you, they will be at a more traditional MUC distance of about half that.

Yes, it’s less expensive, but only by about $6. Maybe life-saving emergency equipment isn’t something to pinch pennies over?

There are just too many reasons it doesn’t make sense. First of all, it’s simply not feasible to carry with you for both practical and social reasons. The cans are just too big. The ridiculous paste-and-post above also claims it “doesn’t attract attention from people like a can of pepper spray would” sitting on one’s desk in the office. Um. What? Unless it’s in a gardening shed, garage, or landscaper’s truck, I think most people would be confused about why you have a can of Raid staged in your cubicle.

Second, there’s at least the possibility of facing legal consequences for using it on a human. Now, the only story I found in which this happened involved wasp spray being used in the commission of a crime, not in righteous self-defense; as such, I think the chance is probably remote if the totality of the circumstances are on your side. Still, the label clearly states, “It is a violation of Federal law to use this product in a manner inconsistent with its labeling.”

Carrying it to protect yourself anyway, whether you’ve read the safety info on the can or not, could easily be construed as premeditation to use a pesticide illegally.

Third and finally, it just doesn’t work. It’s meant to kill insects.

When my close friend Caelan, a dog trainer, informed me that there was OC spray specifically for dogs, that was news to me.

It turns out, SABRE and Mace both sell OC products marketed specifically as dog deterrents. SABRE alleges that only products approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for use on dogs can be used on dogs, and that there is a 1% MCC limit.

What are the EPA’s exact guidelines? Does that mean it’s illegal to use regular OC spray on dogs? Is it illegal to use dog spray on humans?

Unfortunately, I have no fucking clue what the answers to these great questions are: the EPA doesn’t have any publicized, industry-wide regulatory docs that govern dog repellents. That 1% limit doesn’t seem to have any basis in law. Chuck does mention in passing in his article that, “for use on animals, OC spray is heavily regulated by the EPA,” and I trust him on that, but I haven’t been able to corroborate.

For us, though…why bother differentiating? It wouldn’t make sense to carry both dog spray and people spray. You could face civil litigation for anything—including OC spraying someone or their dog—but, as with wasp spray, I’d be far more concerned with whether the circumstances justified it than what product was used.

Caps and Carry Methods

With pepper spray, the form factor of the container matters almost as much as the potency of the spray inside. As you might imagine, the nozzle pointing in the right direction when it counts is a big deal, as is your ability to get a consistent grip that doesn’t block the stream.

While Greg says that, “canisters larger than three ounces are generally too big for daily carry,” I would say that for most people, even something as large as POM’s two-ounce MK3 unit is too large for EDC. I’m a 6’, 176-pound guy who generally wears pants and shorts on the baggier side, but when I try to pocket a MK3, it’s conspicuous enough to invite a “is that a gun in your pants or are you just happy to see me?” comment. Usually it is a gun, but you get my point.

Heed his advice to “stay away from [pepper sprays] disguised as other objects (perfume, pens) and those that are fully encased in some type of sheath that has to be removed before operation.”

We believe in flip-top cap supremacy on this blog. Switch-style safeties are not desirable unless you want a spicy purse or pants.

In my opinion, the pocket clip is the superior carry method. Not only does it keep the spray consistently oriented for a reliable, repeatable grip and draw, but it biases the end user away from carrying it in less-accessible places like in a bag or buried in a pocket with a wad of keys. I can think of at least a few conversations I’ve had with female friends that have gone something like this:

Them: “Oh, yeah, I have pepper spray.”

Me: “Where is it?”

Them: “On my keys.”

Me: “And where are your keys?”

Them: “In my purse…”

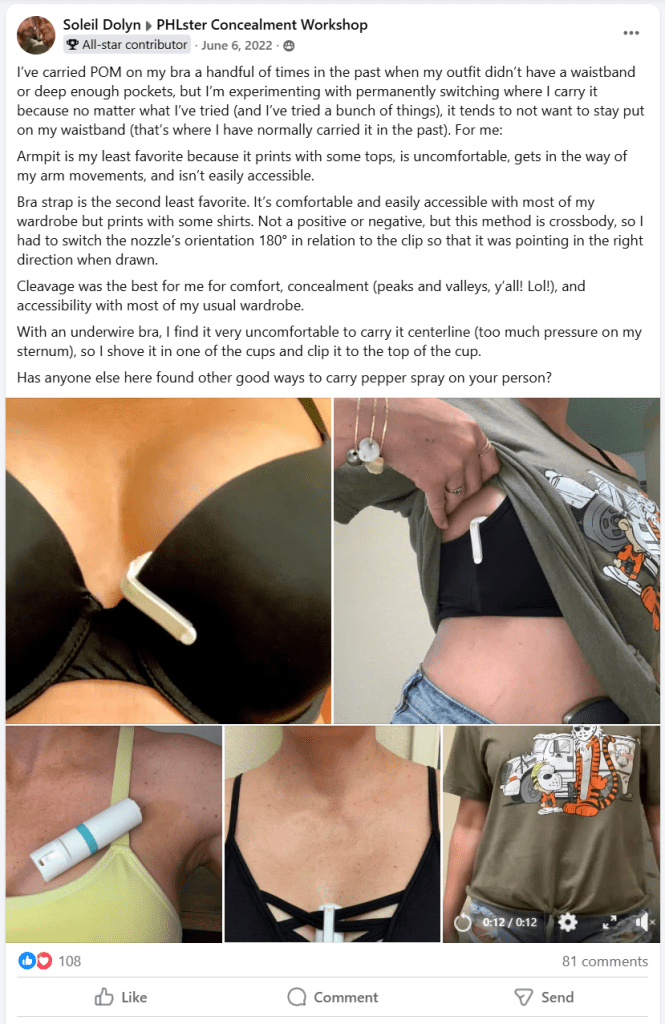

Unfortunately, women are once again at a disadvantage because they tend to wear pocketless pants, leggings, dresses, and skirts. Some helpful ladies in the PHLster Concealment Workshop closed Facebook group shared that they simply use the pocket clip to carry the canister inside the waistband of whatever bottom they’re wearing. An old post from Soleil Dolyn shows several different positions for bra carry with varying levels of concealment and accessibility.

Although POM units win the ergonomics competition by a wide margin in my opinion, there are still some hacks and tweaks carriers can make themselves to improve quality of life:

- The bottom half of the plastic housing on POM units rotates freely around the aluminum canister. This is a feature, not a bug. However, it does mean that it’s possible for the top half with the nozzle to spin out of alignment with the clip, which could be an issue for deployment. Some people choose to tape around those seams with clear Gorilla Tape so that this doesn’t happen; I’ve started using a ranger band for the same purpose. Hockey tape would probably work, too.

- To add friction to the relatively smooth pocket clip, Paul Sharp recommends gluing a small piece of 3M stair tread tape to the inside of the clip and the body of the canister. Andrew Henry, owner of Henry Holsters and POM dealer, includes a length of the correct size of shrink tube with every unit they sell for this same purpose. I’ve also heard of people using silicone anti-slip glasses arm sleeves like the ones below.

- For keychain models, the end user can use or make a lanyard as Mickey demonstrates below. Also consider using a Retention Ring for deep pocket carry.

While some people carry OC on their support-hand side to retain their ability to draw a pistol with their dominant hand, I personally carry mine clipped in my right front pocket. I would rather have the speed and dexterity of my dominant hand to access the spray and then simply drop it, if needed (which I practice in dry fire). One approach might work better for you than the other.

Here are a few pointers for maintenance and EDC:

- Replace your spray well before the expiration date. As Greg notes, “the chemical inside will not lose potency, [but] aerosols tend to lose pressure over time.” I would say it’s good practice to purchase another unit every year on a memorable date like your birthday the same way that you rotate carry ammunition or replace batteries on optic-equipped defensive firearms.

- Periodically swab the nozzle of your unit with a Q-tip twirled into a point. This will keep it free of lint and prevent a partial clog that splits the stream of OC in several directions, spraying back on you in the process. Do not clean the nozzle by blowing it out with canned air.

- Store OC according to its directions. POM and SABRE both advise not to store their spray in temperatures above 120° or lower than 32° and explicitly not to store it in your car. For what it’s worth, I’ve heard anecdotes about potential bursting and leaking, and I’ve heard anecdotes from people that say it’s totally fine and they’ve never had an issue. Apparently, it doesn’t need to be that hot out for the interior of a vehicle to reach that 120-degree mark in a pretty short amount of time, so I wouldn’t risk it. Consider it just another reason to carry everything on-body.

Notes on Deployment

In her article for Shooting Illustrated, Shelley Hill of The Complete Combatant highlights three common mistakes made by students in her Intro to Pepper Spray class:

- Blocking the nozzle with the knuckle of their index finger. If you have big meaty claws, consider adding a zip tie like a Pistol Forum user did (right).

- “Overspraying the target.” A perfect application would see the stream not going past the ears on either side of the deserving individual’s head; anything more wastes time and aerosol pressure. Plus, any spray that misses will stay airborne, waiting blown off course or back into your face by an unlucky gust of wind.

- “Missing the target because the first blast of pepper spray was too low.” Just as there is height-over-bore with a rifle, there is a “‘bent thumb to nozzle’ offset” with pepper spray. Getting the elevation right is a big deal, so learn where and how to get a coarse aim off of the rounded top of your thumb.

Range and Latency

As a general guideline, range seems to scale with unit size, meaning the standard half-ounce, pocket-sized sprays won’t reach as far as the home defense and riot control models the size of small fire extinguishers. The standard for the former seems to be 8 to 12 feet. Wind speed and direction play a part, I’m sure.

Spray pattern is also a factor, though. Here’s what SABRE has to say on that note:

“Pepper sprays using a cone/mist spray fire from 6 to 12 feet (2 to 4 meters). Cone delivery products deploy approximately 10 feet (3 meters) and gel sprays typically spray 20% further than stream.”

I couldn’t tell you whether those averages are accurate or not. Suffice it to say that the best way to determine the practical effective range of what you carry is to test it both with inert trainers and a live unit. The visual understanding you get will be much more useful than 2-D numerical data.

One final note: while many modern pepper sprays are made with what’s called bag-on-valve technology that allows canisters to be held at any angle and still spray, even upside-down, this is not the case with every OC product out there. While I would say that the time for pepper spray has likely passed if you find yourself on your back, it’s worth knowing that it might not even work from on the ground.

In both ECQC and EWO, Craig Douglas points out that in firearms training, time is often thought of clinically. It’s treated like an isolated variable and isn’t often considered in context. The linear relationship between range and time shows that time matters…a lot. By extension, range also matters a lot.

Physical violence happens at contact distance. Since we’re carrying OC to keep standoff between us and a threat of physical violence, the amount of time it takes someone to get within arm’s length needs to be measured against how long it takes to stop them.

It’s for that reason that we have to note that OC doesn’t take effect immediately. Jim Klauba, author of this blog post from the makers of the collapsible batons ASP, puts the timeframe at 30–45 seconds. In an interview, John Murphy of Citizen-Defender (formerly FPF Training) opines that “it takes a few seconds to work,” but doesn’t specify further.

I would say the best mindset is to be prepared for your spray to work very slowly or not work at all.

Blowback and Cross-Contamination

While diving deep in my archive of favorited links to videos and articles I’ve saved on this subject, I reread a post by Annette Evans where she mentioned a method of simulating a partial exposure to OC spray. She had used this method “to demonstrate a limited reaction to a friend.” So, as she described, I test-fired the unit of POM I carry every day and dabbed the tiniest drop of residue left over near the nozzle at the corner of my left eye.

For about 10 seconds I didn’t feel much of anything. The next ten minutes or so were quite unpleasant, with the most significant symptoms being mild lacrimation and involuntary closure of the afflicted eye. And when I say ‘involuntary,’ I mean I literally could not keep it open—which was, ironically, an eye-opening experience. This was nothing close to a full blessing with the hot sauce in both peepers, of course. Still, it was enough to convince me that getting some OC smeared on your face while grappling with a would-be attacker you just hosed down would be bad news.

The topic of Anette’s blog post above was whether the risk of being blinded by your own OC because of shifting wind or spray-back outweighs the reward of carrying it at all.

In my very humble opinion, the risk is real but negligible with the right choice of OC and good tactics.

Fighting Against It

She also addressed naysayers who “argue that pepper spray will, at best, anger an attacker but not do anything useful to stop or disable them.”

It is 100% true that certain high-threshold individuals have insane pain tolerance, and that a person intoxicated or high on hard drugs might be totally analgesic. Still, my understanding is that OC still has a physiological effect: no one is ‘immune’ to it.

Lacrimation and involuntary eye closure should still occur, as even meth zombies have mucous membranes that will become inflamed when exposed to OC.

To me, the whole ‘it will only piss the bad guy off’ argument is too reminiscent of critics who mock the idea of carrying tools because allegedly they’ll be taken and used against the carrier (usually it’s anti-gun folks trying to underscore the lethality of firearms, but sometimes it’s sexists pointing out that men are statistically larger and stronger, as if that’s news to anyone).

Yes, pepper spray might only anger an attacker, but, hell—depending on ballistics and shot placement, bullets might only anger an attacker. There are no guarantees. There’s always a chance your seatbelt, fire extinguisher, or parachute might not work, either, but it’s still no reason not to make an attempt.

What do you do if a criminal sprays you? Again, Greg Ellfritz offers his advice:

- Retreat, if possible. Even if you can’t completely break contact, you should be able to get beyond the range of most pocket- and keychain-sized pepper sprays.

- Cover your eyes with hands, clothing, or other objects to block the spray; alternatively, use something like the horizontal elbow shield that makes up one half of the default position to keep the stream from entering your eyes.

- Experience live exposure beforehand in a controlled setting. Knowing what to expect will make the pain easier to fight through and help you keep your composure.

Palm your POM

Having tools on our person is the first step, but the ability to access those tools when we need them, under realistic circumstances, is paramount. Because of its intended use as a deterrent or preemptive measure, we’re not as concerned about getting pepper spray out in-fight under active resistance. Still, there are considerations for how to bring into play beforehand and what to do after.

In the Instagram reel (right), Craig suggests discretion is needed when drawing pepper spray to avoid escalating the situation, since any bum who might be hassling you knows what it means when someone reaches suddenly for their waistline or pockets. He demonstrates blading oneself to obscure their draw and then concealing the unit in a modified fence position similar to a Chinese fist-and-palm gesture.

If you have to use it, call 911. Just because there’s no spent brass on the pavement doesn’t mean that there’s no race to the phone—you still need to establish your innocence, and being the first to report the incident goes a long way towards that.

Normally, there would be decision to make about whether or not to remain at the scene; most of the time, though, breaking contact will probably be the safest option. If you can justify using physical force, I would say there’s a good chance you’ll be able to articulate why you didn’t wait around for your would-be attacker to regain his eyesight or for his friends to jump you. Use good judgement.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading! We’ll be talking about some other less-than-lethal options—including some variations of pepper spray—in the second post of an upcoming two-part series on women’s self-defense. So, if you want to read about the Byrna, get the verdict on those cat ear keychains that get recommended constantly on TikTok, and see me get shocked with a stun gun on camera, stay tuned.