Welcome, friends. This blog post is the first installment in a two-part series on a topic I touched upon briefly in my review of Calling The Shots by Jenna Meek: the fact that women’s self-defense products suck.

Part 1 will go over the inherent problems with the way that these gadgets and gizmos tend to be pushed on ladies by people in their life, as well as the harmful ways they’re marketed. Part 2 will explore the most common categories, look critically at some of the supposed options in each, and highlight which—if any—could actually be viable for defensive use.

This post is more discussion-oriented than those I’ve published thus far, so if you’re more interested in what the verdict is on the products themselves, tune in for part 2.

Lethality, Liability, and Less-Than-Qualified Advice

Wives, fiancées, girlfriends, daughters, and sisters are routinely subjected to unsolicited recommendations for both widgets and tactics that will supposedly keep them safe. For the most part, these recommendations come from friends, family members, and significant others whose intentions are good. It is the thought that counts, but even when advice is given tactfully and empathetically within the boundaries of what’s appropriate for a particular relationship, it can still be problematic.

The issues lie both in the delivery and in what’s omitted. Let’s talk about it.

Peer Pressure and Condescension

For starters, these well-meaning suggestions are usually made with no consideration for the recipient’s comfort level in terms of what steps they are and aren’t willing to take, and without regard to where they are on their defensive journey.

To people who aren’t ready to take responsibility for their own safety, having a tool thrust metaphorically (or literally) into their hands must be off-putting. Feeling pressured into taking a big step like carrying a lethal weapon would probably turn a lot of women away from the path altogether; and yet, handguns are not uncommon gifts for wives and fiancées. Even the introduction of a less-than-lethal option like pepper spray can be a formidable mental hurdle to someone not used to even thinking about protecting themselves, much less carrying a tool for the purpose.

“Don’t Buy Your Wife a Gun” by Beth Alcazar, USCCA Blog

The psychological resistance and practical objections are both valid. The necessary mindset shift from willful or naïve blindness to vulnerability and agency may be too big a leap to handle. That’s to say nothing of whether or not a person has resolved their willingness to justifiably kill or maim another human being in self-defense, which we’ll discuss more shortly.

Plus, the mental demands and practical realities of living tooled up for self-defense constitute a significant lifestyle change in and of themselves. The physical experience of carrying a firearm, for example, can vary from just uncomfortable to nothing short of a sensory nightmare. Adopting any tool could call for changes to a person’s wardrobe and daily habits.

Unfortunately, as Alex points out in the video below, “sometimes [significant others] will simply quietly go along to not make waves even though they’re not really interested in adopting that lifestyle.” No good can come of that.

Insensitivity can also come in the form of condescension.

It’s possibly even more insulting when these recommendations patronizingly assume that the recipient is not comfortable with or is somehow incapable of ‘handling’ lethal self-defense tools or making defensive preparations that require a bigger commitment.

This is just a more extreme variation on the prehistoric gun shop chauvinism that used to lead clerks to push pink snubby revolvers on clients, as though the fairer sex wasn’t up to the tasks of loading a magazine or disengaging a safety. Instead, the implication is that any type of firearm is too much to manage—better they be equipped with a less-than-lethal alternative.

Not only is this approach insulting, but it’s based on the misconception that tools like pepper spray don’t require any training or practice because they’re not deadly weapons. This brings us to problem number two: what gets left out of recommendations for women’s self-defense gear and tactics.

Instructions Unclear, Killed in Streets

Sadly, the act of recommending (or the actual giving of) some kind of personal safety device—whether a serious tool or just a self-defense ‘product’—isn’t always accompanied by any kind of meaningful guidance on how to use it or any discussion of legality. Although the stakes scale with the potential consequences of misuse, this is negligent any way you slice it. Yes, the severity of the possible negative outcomes might be worse with a gifted firearm than a sharp fixed blade, but neither is something you can just hand over to an untrained person.

This holds true even for pepper spray. In a previous relationship, I made the mistake of thinking a can of POM was intuitive enough that I could hand it off to my ex-girlfriend to carry in the city without an intensive safety brief beforehand. She later confessed that her unfamiliarity had almost led her to negligently discharge it into her own face. Lesson learned.

Even if an item itself doesn’t endanger the recipient or the people around them, the false confidence it often fosters certainly does. As we’ll see in part 2, that’s a recurring theme with many of these so-called personal defense solutions. I’m getting ahead of myself, though.

There are two layers to legality: first is the matter of whether it’s legal to own and carry the tool or product itself and, if so, where. Second is what level of force actually using it would constitute, and, accordingly, the circumstances that could justify that. Both need to be discussed beforehand but aren’t always, in practice.

Much Safe. Very Empowerment.

A pushy or negligent middleman can lead to uncomfortable situations and bad outcomes for aspiring female self-defenders, certainly. But the women most at risk are those who don’t know what they don’t know and are all the more likely to get conned into purchasing gimmicky protective devices as a result. It’s ironic that those who may be most concerned about their safety are the ones being preyed upon by pandering marketers. And no, that’s not victim-blaming.

The advertising tactics I’m referring to aren’t exclusively used by sellers of talismanic, impractical trinkets, but those sellers are the usual culprits.

A red flag that I see repeatedly in the marketing copy for these products is the use of the word ‘feel.’

To see what I mean, take a look at a few blurbs below from the descriptions and testimonials for items in the dishonorable mentions category in part 2:

- “Just the act of holding ____ in your hand will ensure that you have a heightened sense of your surroundings, making you feel less vulnerable and more confident.”

- “A ____ is a fantastic self[-]defense solution if you are looking to feel safer and well-prepared when you are outdoors.”*

- “I live off-campus now as a college student and I have to walk alone in the mornings to work[,] so ____ makes me feel so much safer!”

*This item is actually not going to appear as a dishonorable mention and could actually be viable, but I needed a third bullet point and the sentiment is just the kind of thing I’m talking about. Don’t click or mouse over the links unless you want spoilers.

Of course, feeling is not the same as being. It’s not objective. I may feel like a competent grappler against the middle-aged father of two who’s been training BJJ for half as long and rarely has time to work out, but put me up against a 130-pound high school wrestler and suddenly my feelings no longer matter.

It’s true that makers of legitimate defensive tools take a similar approach, selling confidence as much as their products themselves. For example, an ad from Smith & Wesson’s 2022 catalogue reads, “WHAT SECURITY FEELS LIKE.” The most popular brand of OC spray in the defensive training community, POM, stands for ‘peace of mind.’

The difference is that those things have a realistic chance of stopping an attacker. That’s my take on it, at least.

Do the empowerment peddlers know the wares they’re hawking are often no more useful than good luck charms?

Either way, this brings up larger, overarching question…

Mars and Venus

Why are women the target demographic for all this gimmicky marketing, and not men?

It seems to me that the average woman is subjected to a great deal more fear-based messaging when it comes to their safety than the average man is. This is obviously not without some reason. I’m not exaggerating when I say that the majority of women I know currently and have known in the past have been victimized in some way, to some degree. I wish that was hyperbole. In any case, this marketing trend both exploits those legitimate fears and perpetuates them.

It could be that men gravitate more towards traditional [lethal] tools because of social and gender norms. As Phil Elmore suggests, “it may also be the case that, per the old Onion headline, the average man is 10,000 percent less effective at fighting than he thinks he is, so he’s less likely to take the ‘quick’ solution because of false confidence.”

But, as he goes on to say, what it probably boils down to is that, overall, women are just less interested in self-defense.

There might be biological and genetic explanations for that, but whatever the reasons, the evidence is hard to deny: in my experience, the ratio of male to female students in firearms courses where both sexes are present is tremendously lopsided, if there are any women attending a given class at all. In martial arts like wrestling, jiu jitsu, and MMA, men typically outnumber women ten to one—and those women who do train are, shall we say, built different. Different in a good way, to be sure, but still outliers. The careers and backgrounds that most instructors hail from (typically the military, law enforcement, and competitive shooting) are likewise predominantly male.

Because there are fewer women in the circles of people who make it their business to test which tools and techniques work in violence, they end up “under-represented in serious self-defense study.” Generally, the individuals who engage in this kind of testing identify themselves as practitioners of combatives, which Guy Schnitzler defines simply as, “an integrated, multidisciplinary approach to fighting with and without weapons.”

“Personal-Protection Practices: Does It Work for You?” by John Johnston, Shooting Illustrated

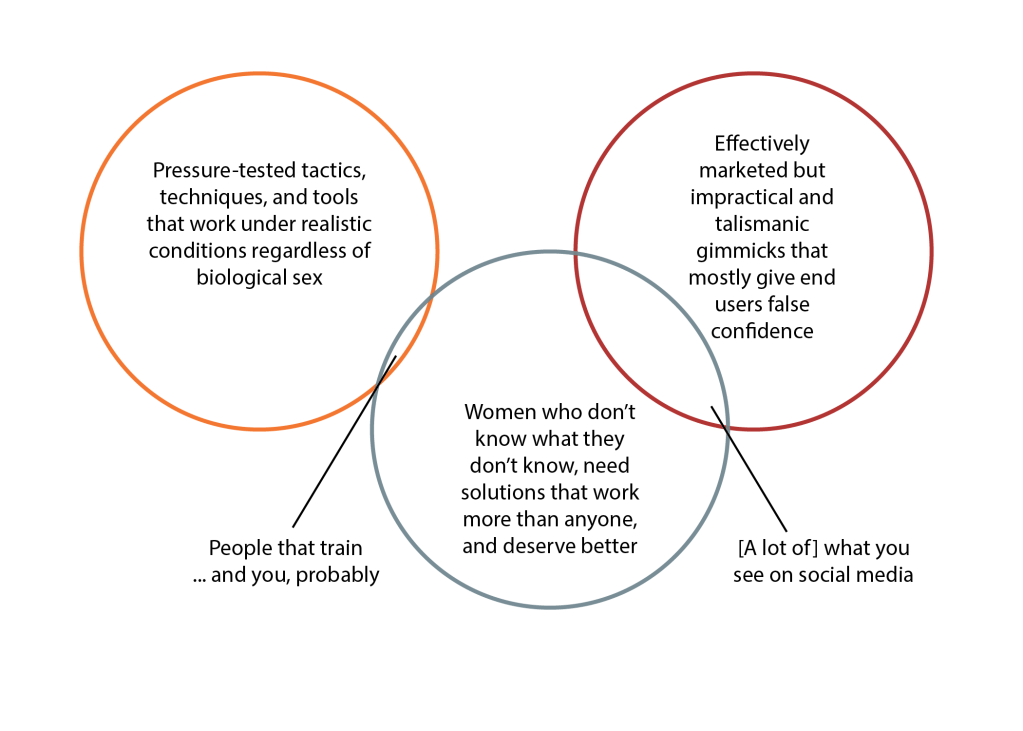

Here’s my conclusion: there are two main groups of people involved. One is the thought leaders in the discipline of combatives, in which we’ve already established women are under-represented. The other is the commercial vendors of general population self-defense products.

The issue is the two don’t talk.

So, what ends up happening is the people who know what they’re talking about don’t reach the average woman, who needs solutions that work more than anyone. The companies that do reach female customers have no idea what real violence entails, so the products they come up with are feel-good quick fixes and cheap trinkets that appeal to those with the least information.

But here’s the biggest reason the market is dominated by rhinestone-studded keychain pepper sprays and personal alarms.

Most women, like most people, aren’t that serious about self-defense.

The average American wants to find simple solutions, take a few easy steps that will make them feel safe, and expend as little time, money, and energy in the process as possible. It’s not a sex-specific attitude. Let’s face it: we live in a culture that prioritizes short-term comfort and convenience and biases us towards purchasing solutions to our problems.

My training partner Aaron pointed out that the only difference between men and women in this regard is that the items men buy and carry around as defensive talismans are far more dangerous. At its root, it’s mindset problem. It’s probably no more prolific among one sex than the other—it just manifests itself in different ways and is dangerous for different reasons.

Conclusion

So, to sum up, it’s not just that the products women get recommended suck, which—spoiler alert—they mostly do. It’s that people deserve respect for where their minds are at regarding self-defense. If a loved one wants to start training and carrying tools to protect themselves, do your part to read them the fine print about using force and iceberg of legal issues that implicates. Don’t lecture, just gently stress the importance and nudge them towards the information they should be pursuing on their own. Encourage them and give them space and time to grow.

Basically, don’t be that guy…Or that gal. Or that nonbinary person. Just don’t.

If you take one thing away from this, let it be that the majority of the tactics, techniques, procedures, and tools of self-defense are the same for men and women because the goals are the same. Are some of these affected by changing the variables of height, weight, and strength? Of course. But if, for example, a given technique allows a self-defender good ability to break an opponent’s posture or control their hands even if that opponent is taller, heavier, and stronger, why would a burly, muscular dude not want to use that same technique?

Want to learn legitimate skills to protect yourself? Stop by Stout PGH’s new Strip District location at 5:30 PM on Thursdays for self-defense with Misti.

I know we touched on some contentious issues in this one, so if you disagree, feel free to let me know in the comments. I would love to start some dialogue with anyone who has differing opinions! In any case, thanks for reading. Until next time!