Welcome, friends.

This blog post is the follow-up to my recent commentary on the marketing of bullshido and gadgets to women for personal defense. We’ll take a look at the categories those gadgets fall into, a few specific examples from each, how they work (or don’t), and some legal considerations.

Some of the items we’ll discuss today can rightly be called tools, but ‘products’ is really the only word that fits for many of them.

Options…Or Are They?

‘Safety products’ for women are a racket. A lot of these gadgets and widgets must seem hokey even to them. But are there viable defensive tools among the nauseatingly pink and rhinestone-studded sea of seeming bullshit? Let’s talk about it.

Pepper Spray

Pepper spray, also referred to as OC spray or mace (although the lattermost is a registered trademark that has come into use as a generic term—more on that later in this post) is touted as the go-to solution for everyone from college coeds to joggers to soccer moms.

Since I’ve already written about pepper spray at excessive length in September’s blog post, I wanted to focus on some alternatives that are in the same family but purportedly distinct from the simple aerosol units people tend to carry.

These relatives can be categorized in three groups:

- Pepper projectile launchers like those sold by Byrna, SABRE Red, and PepperBall. These are sort of like CO2 paintball guns that shoot OC-infused ammunition.

- Pepper spray ‘guns’—basically, pepper sprays in dispensers with pistol grips and triggers like this one sold by Mace. SABRE has their own version, and for a time they sold a similar version in collaboration with Ruger, but that one appears to have been discontinued.

- Oddballs like the Kimber PepperBlaster 3 and ASP Defender series. I’ll talk about each individually.

Projectile Launchers

To write this blog post from a more informed perspective, I sat down with Patrick Cranston: wrist-locking purple belt at Stout PGH north and owner of Paratus Self-Defense LLC. As a Byrna distributor, he was able to answer some questions about their finer points and let me test-fire one to get some hands-on experience.

“Byrna SD Less Lethal Launcher Review [2024]” by Daniel Reedy, Primer Peak

I asked Patrick for his honest perspective on how launchers like the Byrna stack up to conventional pepper spray. After all, even though their manufacturers try to set OC launchers apart as distinct alternatives to pepper spray rather than competitors, aren’t they essentially trying to be the same thing: ranged less-than-lethal tools?

Based on his response and what I learned from test-firing a few of the floor models, here are my two cents:

- Although I only fired the inert kinetic rounds, demos of the OC projectiles show a cloud of powder being released. This creates a sort of ‘area of effect’ phenomenon, so less precision is required but respiratory impairment is just as likely. It could also be used like an area denial weapon in a home defense scenario in the same manner as fogger or bear-spray-sized OC units, since the airborne powder can linger in an enclosed space. Distance from the breaking projectiles also makes cross-contamination potentially less of a concern.

- There is no FFL transfer fee, no form 4473, and no NICS check when purchasing a launcher, nor is there duty to inform during a traffic stop or other legal headaches when traveling across state lines while transporting it (though, if you’re pulled over, there are probably circumstances when it might be prudent to mention you were carrying one anyway). Traveling by air restricts you to kinetic projectiles only, but it should still be a legal option wherever you land. I haven’t become a lawyer since I last posted though, so as always, check your local laws as well as those of your destination and any state you’re traveling through to get there.

- Whereas pepper spray expires, the Byrna products in particular use patented technology that allows you to stage the launcher indefinitely with a loaded magazine and full CO2 cartridge, which is sealed until punctured by the first trigger press. Contrary to what Mr. Reedy wrote in his review, I did not find that first trigger pull was “much heavier” than subsequent presses because of this. Maybe I’m just stronger than I think.

Having said that, I still see several potential issues with OC launchers:

- Adds complexity to EDC. It’s quite easy to carry both a concealed pistol and pepper spray without feeling over-encumbered or too tool-dense around the waist. However, I think it would be pushing the envelope to try and conceal both a handgun and even a compact Byrna, for example.

- Feels like a gun. In relation to the above, if you’re carrying both one of these or a TASER and a pistol, be aware of at least the remote possibility for a loud and potentially lethal mix-up.

- Looks like a gun. I personally wouldn’t want to be holding anything remotely gun-shaped when responding officers arrive on scene. I especially don’t love the idea of them pulling up adrenalized and white-knuckling because some bystander called in about a crazy guy with a gun, and dispatch telephone-gamed that into ‘active shooter.’

I’m also not sure of the legality of a defensive display with a launcher. Even in orange or yellow, they could easily be mistaken for a gun with a Cerakote finish. In the wrong jurisdiction, I don’t think it’s totally out of the question that you could be charged with making a terroristic threat. Plus, what happens if the ne’er-do-well you brandish your launcher at doesn’t just try to get you in hot water with law enforcement after the fact by claiming they thought it was a gun—what if they’re actually convinced it is one in the heat of the moment, and start blasting with one of their own? - Costs more. Like I said in my planning post for the book that this blog will eventually get turned into, I respect money as the primary limiting factor it is with regard to most people’s self-defense preparations. And the price difference between a $12 or $20 unit of POM and even the cheaper SABRE launcher is significant.

One note on the first bullet point: if I did decide to carry a launcher in addition to a pistol, I would invest in a custom kydex IWB holster and carry the launcher behind my support-side hip. That way, my dominant hand would be free to draw a pistol. I also think it would go a long way towards eliminating any potential confusion over which tool is which—a big deal, since the Byrnas do feel quite a bit like striker-fired guns in hand.

In my eyes, less-than-lethal launchers have the most appeal as gateway or training wheels ‘guns.’ They’re still ostensibly useful for self-defense with far less liability than a real firearm. Form factor permitting, I think concealing a launcher for a few months could be a great way to build someone’s comfort level with EDC.

Sprayguns

These are essentially pepper spray in a different-shaped dispenser. The first and third ‘con’ bullet points under the OC projectile launchers section apply here, as well.

…especially the first. To anyone that knows anything about holsters for pistols, one look at the manufacturer offerings is enough to know they’re not street-ready, or anything-ready, for that matter.

Ordering a custom kydex holster for an OC launcher that costs as much as a handgun makes sense, in my opinion, but not so much for a disposable $50 spraygun. I would forget about carrying inside the waistband altogether. The Mace Pepper Gun seems bulky, and even the more compact-looking SABRE spraygun comes in at a chonky 1.5” wide.

Oddballs

In this category, we have two products to look at.

Kimber PepperBlaster

The Kimber is one of the pepper spray derivatives that Lucky Gunner tested in the video I embedded in the post on that topic. You can find the transcribed video at the link below.

“Choosing Pepper Spray for Everyday Carry” by Chris Baker, Lucky Gunner Lounge

The PepperBlaster 3 is a two-shot OC derringer that fires jets or blobs rather than a stream or mist. Whereas typical pepper spray is dispersed by compressed nitrogen, those jets are launched by a pair of small pyrotechnic charges that accelerate the spicy brew to 112 miles per hour with a 13-foot range. Because of this, Kimber claims, not only is the mixture not diluted by propellant, but “there’s no way it can lose pressure over time.” Despite this, it does have a four-year shelf life.

Being sold by a gun manufacturer, the obvious intended market for the PepperBlaster is self-defenders with firearms experience who want a familiarly packaged less-than-lethal tool: it has a trigger, sights, and a finger shelf grip.

Notably, Kimber’s formulation tops out at 2.4% Major Capsaicinoid Content: almost double the heat packed by POM, and even hotter SABRE’s bear spray.

Although it performed pretty much as advertised in Chris’s test, the biggest reason it gets a pass from me is that it could seriously injure someone. Kimber’s instruction and safety manual for the PepperBlaster say as much—its minimum safe discharge distance of two feet is mentioned no fewer than seven times.

Writing for American Cop, Eugene Nielsen says the potential for eye injury is “due to a phenomenon known as the ‘hydraulic needle effect.’” This is a term I first heard about from my mentor James Ashbaucher, and read more about in the old Marine Corps OC handbook embedded below.

It occurs when “OC particulate [penetrates] the soft tissue of the eye,” potentially causing “injury, prolonged irritation, or possibly infection.”

While OC is ideally used at ranges beyond two feet anyway, I’d still rather not maim an assailant who was able to get that close. And, for the, ‘well, I would never let him get that close!’ crowd, managing space and setting verbal boundaries is harder than walking and chewing gum at the same time. I promise.

ASP Defender Sprays

The last pepper spray product we have to discuss comes from ASP, of collapsible baton fame. These are cylindrical, keychain style sprays that disperse OC from one end rather than a nozzle on the face of the cylinder. They’re meant to be indexed horizontally near the neck or jaw similar to the flashlight technique; a hinged, curved lever-style safety must be flipped before using the thumb-actuated trigger opposite the business end. Currently, ASP sells four variants: the Sport Defender D1 and D2, and the Metro Defender D1 and D2, with the D1 models being shorter at 4.22” and 4.5” compared to 5.6” and 5.75”, respectively. The main difference is that the former is made with a polymer housing, the latter with one machined from aluminum.

Note that the advertised range of these sprays is just a measly five feet. The spray pattern is a fine jet of mist that looks like it would have considerable respiratory effect, so a few half-second bursts could end a confrontation promptly, but that isn’t much standoff distance to work with if it doesn’t.

I would go with the Metro Defender D2 over the Sport Defender D2 for the aluminum housing and aggressive knurling. Empty-then-drop-it could be a valid strategy for this style of spray, but having something close to a purpose-built impact weapon already in hand seems like a good idea given their short range. Chuck Haggard corroborates in the RECOIL article I cited in the pepper spray post, writing, “strong-hand use allows me to instantly transition to using the sprayer as an impact device, using the Pikal jab techniques taught by famed trainer Craig Douglas.”

Overall, these look like they could work well for EDC. At about the length of a pen and a little over six tenths of an inch in diameter, pocket carry is a viable option and the split ring gives you a second method, if needed. I’d love to get my hands on one and some inert training cartridges to play around with.

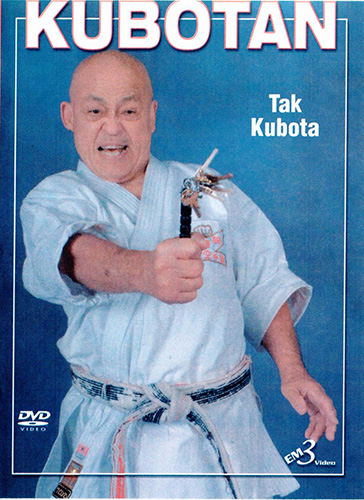

Kubotans

A kubotan is a short cylinder or rod that can be used as an impact weapon. They are typically between 5 ½” and 7 ½” long and often have a keychain split ring at one end. Some are plastic; some are steel or aluminum. Some are flat-ended or have blunt or rounded points, and some are downright icepick-like.

While conceived of by its inventor Takayuki Kubota as a tool strictly for pain compliance via a variety of joint locks and pressure points, I feel like using it against a motivated attacker would quickly devolve into a barrage of frenzied hammer fists. So, any bid for less-than-lethality is subject to it not being used to dent skulls and snap metacarpals, and I dare say that would be the more natural reaction in an entangled fight.

These applications arguably made more sense in a law enforcement capacity where gaining submission and control were part of the Mission. For civilians, a kubotan might still be useful to concentrate the force of strikes onto a smaller surface area in order to break grips and make space, although that’s not what it was originally intended for. Randall Chaney, writing for Springfield’s The Armory Life blog, notes that there are similar tools from judo and Filipino martial arts that are meant to be used in that manner, but that the kubotan is different. For the modern self-defender, though, I don’t think it really is.

Because even simulated violence can get so kinetic and dynamic, I’m not sold on the viability of gradually applied pressure points to subdue an attacker. Even without strikes in the mix, precisely targeting a pressure point with a forceful push seems implausible. Swinging a hammer fist, less so.

When being used in a keychain role, one can supposedly also grip the length of a kubotan and use it like a tiny flail. Let’s just say I’m skeptical. For one thing, how many metal keys does the average person even carry nowadays? Getting hit in the eye with a plastic key fob doesn’t sound quite as effective as taking a half dozen tiny, serrated blades to the face. Either way, I’m not sure what the fight-stopping efficacy of this technique could possibly be.

Lastly, one of the supposed pros of the kubotan is that is “harmless-looking,” in Kubota’s own words. “When asked, ‘What is that funny looking thing?’”, he writes in the manual, “you can honestly reply: ‘it’s my key chain.’” With one of the more innocuous iterations like the original, you might be able to get away with that. But even an idiot knows a weapon when they see one. As a point of reference, the TSA forbids kubotans by name in carry-on luggage.

Are kubotans better than nothing? Probably, yes. If it were me, I’d opt for one made of metal that’s rounded or blunt rather than pokey, with as much mass as possible, to have physics on my side. All things being equal, I’d probably rather have a solid flashlight. A good one from SureFire or Streamlight is more than sturdy enough to be used to beat the snot out of an attacker…while also being a flashlight (which you should be carrying anyway if you carry a pistol). Chances are, a flashlight is legal in more places, too, provided the bezel isn’t spiked or crenellated too aggressively.

Are they a good choice for women? That’s hard to say. I think a kubotan could be a force multiplier, but regardless of sex, they do seem to favor users with boxing or Muay Thai experience who have a good eye for range and some striking fundamentals to fall back on.

All I’ve said thus far also applies to so-called tactical pens. While the right one could be good option for a nonpermissive environment, overtly weaponlike ones with prominent ‘glass-breaking’ tips won’t fool anyone. But they, too, could be useful with the same techniques.

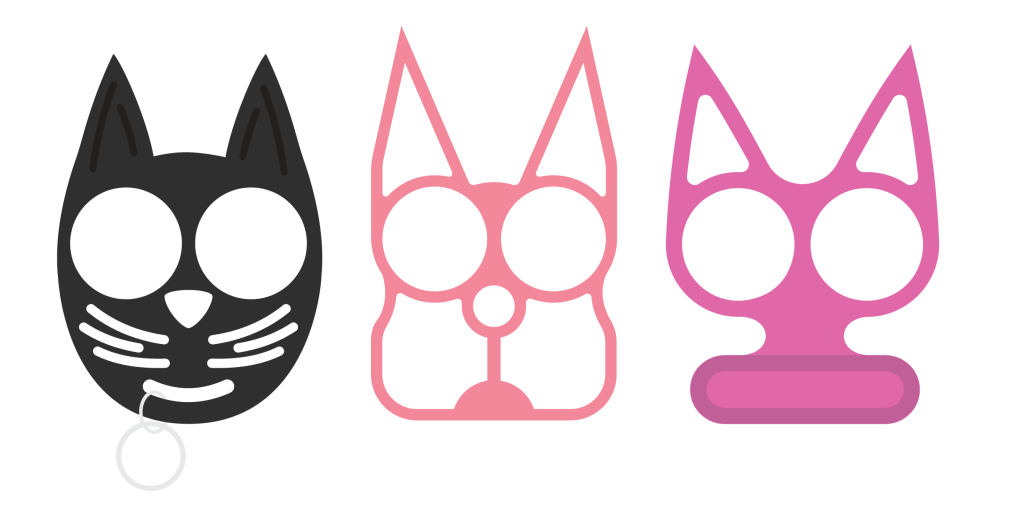

Cat Ear Keychains

I hate these things. For starters, even mainstream ‘journalism’ admits that they’re illegal where brass knuckles are illegal, which is quite a few places.

Pennsylvania Criminal Statutes Title 18 § 908 (prohibited offensive weapons) explicitly singles out metal knuckles as being illegal, so aluminum kitty ears like these ones from BUDK, shown left, could almost certainly land you in hot water legally under the wrong circumstances.

Does that mean iterations made of injection-molded plastic or resin are fine in PA, then? I wasn’t able to find evidence to the contrary…but, personally? I wouldn’t bet on it. It makes more sense to go with OC, which is legal everywhere in most states except for in NPEs.

Plus, as Anette points out in her post, the thin profile of metal knuckles like those above could lead to cuts or even degloving injuries. Don’t Google that if you’re squeamish.

We should also mention the whole keys-between-the-fingers trick. This needs to die just like the urban legend of plugging a gunshot wound with a tampon—and dying it currently is, although you’ll excuse me if I help it along some by metaphorically smothering it with a pillow in its hospice bed.

You’re liable to cut your hand open with the first blow as the keys fold back into your knuckles.

I would rather use a dedicated kubotan, use a thumb-reinforced grip like the one shown at 6:37, or maybe even grip it like a tiny push dagger, size and shape of the key permitting.

At the end of the day, could you protect yourself with either your keys or one of these keychains? Probably, yes. I was able to find two news stories about incidents in which women used their keys to stop an attack:

Florida woman fights off attacker in apartment complex gym

Woman uses keys to defend herself from attack

That still doesn’t mean I would endorse them as a viable solution, though. I’m no expert on bad guys like Ross Hick is or William Aprill was, but I assume motivation to be a sort of sliding scale. At the low end are perps that are easily deterred by situational awareness and body language; their opportunism or laziness make it easy to deselect yourself. Moving up some, we have criminals that are dissuaded by MUC verbal boundary setting and distance management. Then, attackers who will initiate the assault but are deterred by pain. Finally, I imagine there are some attackers who—depending on the circumstances of whatever drugs their on, whatever delusional state they’re in, or what your personal relationship with them is—will stop at nothing to murder the fuck out of you. Only unconsciousness or death can stop them.

Hopefully none of us is very likely to run into the Terminators at the extreme end. Personally, though, I’d like my solutions to work on even them, which is why we place so much emphasis on tools that are effective on a physiological level.

What saved these women wasn’t their keys. It was a mindset that said, ‘I refuse to be victimized.’ There’s a reason that Active Self Protection’s tagline of “attitude, skills, plan” is in that order. The truth is, sometimes anything works in self-defense. Sometimes nothing works. Our best bet is to make our peace with mortality and train (and equip) ourselves the best we can.

Personal Alarms and Panic Buttons

Analogue rape whistles have become the butt of jokes, yet a gaggle of companies sell personal alarms, which are essentially the electronic equivalent. These are simple, battery-powered piezoelectric buzzers activated by a button or pull pin that emit a loud (130 decibels seems common), birdlike trilling. They ostensibly have two main purposes: to deter an unmotivated attacker or, in the event of a committed attack, draw attention so that a bystander will come to your aid.

It only takes a little secondhand knowledge of violence to see that any strategy dependent upon the arrival of a second party is no strategy at all. As with the ‘just call the police’ approach, the problem is that no one else can be there to intervene faster than you will need to respond.

Young children are perhaps the only demographic that personal alarms make sense for: they are not responsible for or capable of protecting themselves, and their parents or guardians are rarely far away, so there is a more specific first responder within earshot than just ‘somebody, anybody’ to be alerted. As kids grow into teens, alarms can probably take a backseat to OC spray and martial arts; they’ll inevitably start driving and pick up part-time jobs, so mom and dad will no longer be as omnipresent.

“13-Year-Old Girl Uses Jiu-Jitsu To Stop Attacker, Breaks His Ankle” by Ognen Dzabirski, BJJ World

TASERs and Stun Guns

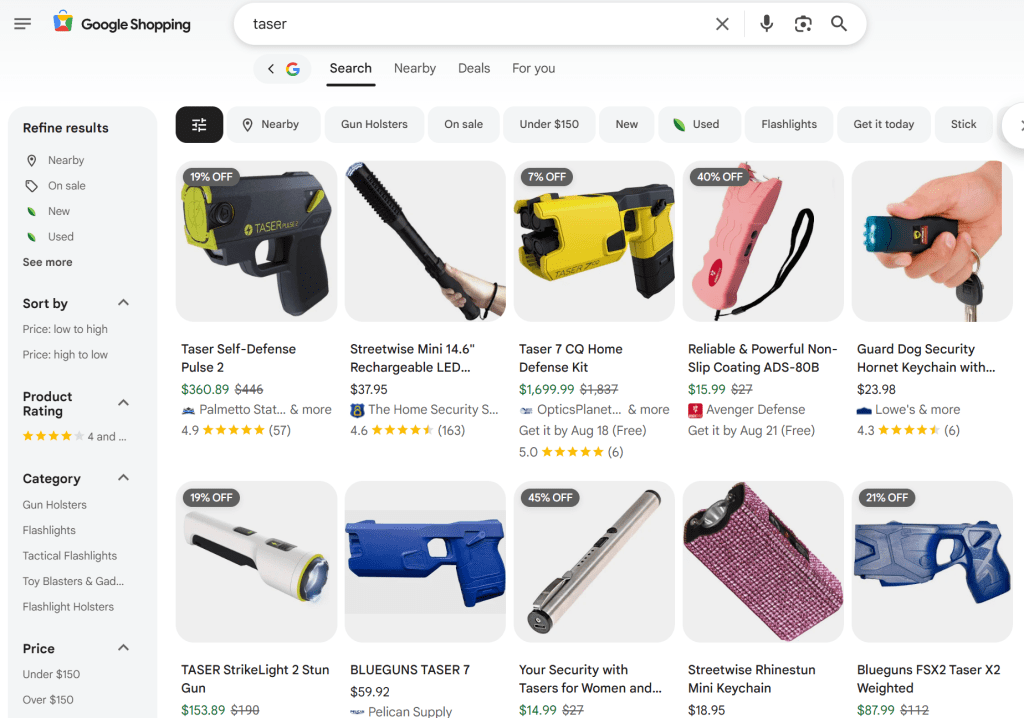

When you do a Google search for “taser” and click over to the Shopping tab, why do some of the items listed cost hundreds of dollars while others are less than twenty bucks?

If you guessed that it’s because there are two completely different types of products shown, you’re onto something.

In the same manner as Band-Aid, Jell-O, and Aspirin—all of which are trademarks that have become genericized—TASER is often used as a catch-all term for any self-defense tool that uses conducted electricity to stop an attacker. While there is a simple linguistic explanation for this phenomenon, the implication that TASERs might be the same as stun guns and vice versa is a potentially confusing one for consumers.

“Stun Guns vs. TASERs: Which Should You Choose?” by Scott W. Wagner, USCCA Blog

TASER is a brand: one known for its ranged conducted energy weapons, which fire pronged darts propelled by compressed nitrogen gas from replaceable cartridges. Connected to a battery in a grip module or handle via lengths of insulated copper wire, these darts embed themselves in a target to create a closed circuit; electricity from the power source is then conducted through the wires and into the target. The result is a state of neuromuscular incapacitation (NMI). The electricity stimulates muscle contraction that temporarily locks up the target’s body. Once the loaded cartridge has been fired, some models can also be used in a contact-stun or ‘drive-stun’ mode.

50% of The Time, It’s 100% Effective

When you ask LEOs how often a TASER works under field conditions, ‘about half the time’ is a common answer.

There are a few reasons for this. For starters, both prongs have to embed themselves in the target. In the words of cop YouTuber Donut Operator:

“If one prong hits a person, the TASER doesn’t work. If one prong hits somebody’s belt, the TASER doesn’t work. If one prong hits somebody’s thick jacket, the TASER doesn’t work. If the TASER doesn’t work, the TASER doesn’t work.”

Another is that, according to AXON themselves, “it is recommended that [the] probes be at least 12 inches apart to maximize the effects of NMI.” Insufficient prong spread could mean little to no effect.

Basically, 50% of the time, it’s 100% effective. The other 50% of the time, it’s 0% effective.

Less-Than-Lethal…Usually

The main selling point of the TASER is that it’s a ranged tool capable of inducing a temporary physiological stop without killing or maiming its target. And it doesn’t…Most of the time, anyway.

While death and serious bodily injury from TASER use seem to be incredibly rare, the literature suggests there are three primary mechanisms by which these anomalies occur: falls, eye injury, and fire. When neuromuscular incapacitation is achieved, the target obviously can’t break their fall, so brain injuries and cervical fractures are a possible unintended consequence. There’s a potential risk of ocular trauma, as with any projectile weapon; the above article references “cases of unilateral blindness from a probe eye penetration,” which I guess is better than bilateral blindness, but still doesn’t sound like too much fun. Finally, there have been a handful of burn deaths from the ignition of flammable fumes like gasoline and methane by arcing electricity.

Don’t get me wrong: the number of taser deployments that don’t result in any kind of complication is astronomically high compared to the number of those that do—6.7 deaths per million field uses and 6.4 injuries per million field uses, according to Kroll’s study.

Still, the bottom line, for me, is that if your go-to less-than-lethal option is relatively expensive, shoots tiny, potentially eyeball-impaling harpoons every time you use it, and is only effective about half the time…There might be better options.

You may be wondering: could being threatened with a legitimate TASER be considered a deadly threat? After all, if you carry tools, being totally immobilized would leave you helpless to resist being disarmed.

This is true, but as Greg says in his post on fighting against a criminal armed with pepper spray, you can’t shoot someone because of something they might do. “We need reasonable, articulable facts that would lead a person in a similar situation to believe that a disarming attempt was [imminent],” he writes. Unless the attacker announces their intentions aloud, the first warning we’ll likely get is them grabbing for our gun as we’re convulsing on the ground—and by that point, it will be too late.

Thankfully, there are ways to counter a TASER being illegally used against us (from the above-linked article):

- If it’s not possible to get out of range, become a moving target, since “both probes have to hit you” to incapacitate. I might even try to ‘bullfighter’ a heavy coat in front of me or use an environmental shield like a chair, cushion, or furniture to block the darts.

- Close the distance to prevent the prongs from getting the spread between them required for the full neuromuscular effect. Tip: assume the default position to prevent a dart to the cornea.

- If you are hit by the TASER but can still move, try and break the wires. Greg notes that “sometimes the darts will be too close together or one dart won’t fully penetrate.” In this case, you’ll still get shocked, but it will feel like only a stun gun. “If you can move,” He goes on, “drop to the ground and start rolling over the wires,” which will either break them or dislodge the darts.

- If you do go into neuromuscular lockup, rip out the darts as soon as you regain motion. The shock on the police version lasts five seconds, and the civilian versions last 30 to give people a chance to run away. Unplugging yourself will prevent another shock from being triggered, and incapacitating you again.

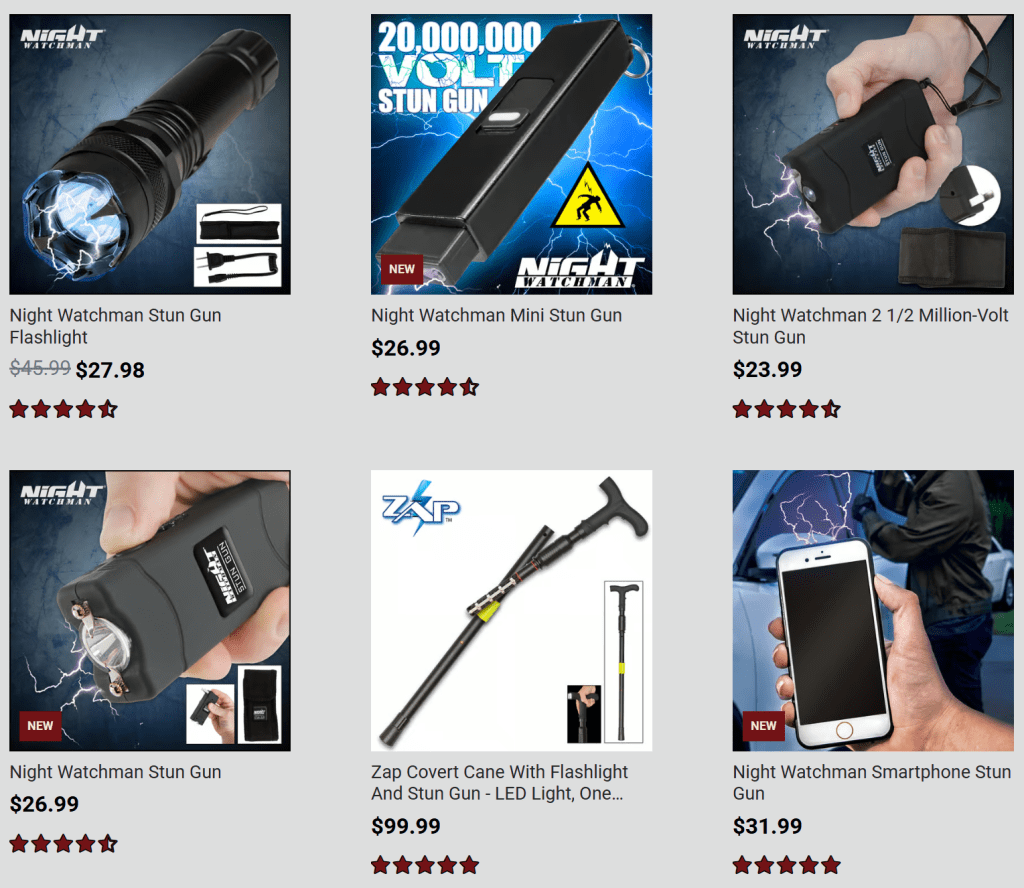

Set to Stun

By contrast, generic stun guns are exclusively contact-range tools that rely solely on pain compliance to stop an attacker. A pair of electrodes at the business end apply the electricity directly to the target, not at a distance as with TASER barbs. One could argue that the visual and auditory stimulus of an arcing stun gun could be a deterrent, which may be the case.

As I wrote in a previous blog post, psychological stops are inherently unreliable compared to physiological stops.

In a moment of impulsive bravery (or reckless stupidity), I decided to experience a stun gun firsthand to confirm this.

My training partner Aaron did the honors—a little bit too enthusiastically, some would argue, but what are friends for? It definitely hurt, but I feel like I could fight through it if my life depended on it. If I put myself in the shoes of a motivated attacker, as weird as that is to write, I’m not sure it would’ve stopped me.

Plus, I was tense, nervous, and had cooled off after training. I think if we had been on the mats with gloves, mouthguards, and headgear—blood pumping and even a little bit of adrenaline flowing—it would have been easier to grit my teeth and power through.

Volts and Amps

Things were already starting to feel too science-y for me just scratching the surface of SHUs and high-performance liquid chromatography to write about pepper spray, so trust me when I say that electricity is complicated. The technical subject matter is further obscured by confusing marketing.

From what I’ve seen, most generic stun guns are advertised with voltage listed or no specs at all. For example, this aluminum stun baton is said to deliver 5,000,000, and this shiny rhinestone one is labeled at a whopping 10,000,000.

According to the University of Calgary’s Energy Education Encyclopedia, “domestic electrical outlets supply 120 volts.” You might be asking, how can it be that a fork in a socket can electrocute a person to death, but a stun gun that’s allegedly tens of thousands of times more powerful doesn’t fry an attacker like an electric chair?

“Study of Deaths Following Electro Muscular Disruption” by the U.S. Department of Justice

Good question. To answer it, we need to define some key terms. For better or worse, as was the case with pepper spray, the best explanations of those terms are provided by a seller of the product we’re discussing—in this case, SABRE. They appear to have used analogies from the USDOJ National Institute of Justice report linked above. Here’s how SABRE put it:

- Volts (V) are units of potential electric current, analogous to the pressure behind a water main—or a pump, if you have well like my family’s house.

- Amperes, or amps (A), are units of electric current, analogous to the rate of water flowing through a garden hose.

- Microcoulombs (µC) are units of delivered charge, “analogous to the volume of water delivered by a hose during a set period of time” (quoted from the report, emphasis mine). It is a measure of current over time.

To paraphrase, you can turn the knob on the spigot all the way on, but the plants you need to water will stay dry if the rate (current in amps) is zero. Even though the water pressure (potential force in volts) is high, the flow is nothing. But with enough water pressure and fast rate of flow, your plants get a lot of water on them (the delivered charge in microcoulombs is high).

This article uses the similar analogy of a river running down a hill to explain voltage.

Basically, it’s the current, or amps, that is dangerous. It’s possible to high voltage without any moving current (amperage). Plus, once you start adding the human body into the equation, you have to account for resistance (measured in ohms), which I won’t begin to get into.

In a sense, according to SABRE, microcoulombs is to conducted energy weapons what major capsaicinoid content is to pepper spray: the true measure of effectiveness. The NIJ report states that 1 microcoulomb causes “intolerable pain.” Since stun guns are pain compliance tools, from SABRE’s perspective, that’s the only measurement that matters.

The one I got shocked with hurt quite a bit, but maybe not all stun guns are created equal? In the video below, Annette Evans doesn’t even flinch.

I haven’t tried them all and really don’t want to, but there might be better options than stun guns from a physiological perspective.

Legality

If you read the statute on prohibited offensive weapons I cited above when discussing cat ear keychains as brass knuckles, you might’ve noticed that it also criminalizes the use and possession of “any stun gun, stun baton, taser or other electronic or electric weapon.” Turns out, Title 18 Section 908 was amended in 2018 by a subsection, which reads:

“A person may possess and use an electric or electronic incapacitation device in the exercise of reasonable force in defense of the person or the person’s property pursuant to Chapter 5 (relating to general principles of justification) if the electric or electronic incapacitation device is labeled with or accompanied by clearly written instructions as to its use and the damages involved in its use.” (Note: the hyperlink is my addition and isn’t present in statutory text)

That doesn’t apply to individuals prohibited from possessing firearms, however. If you have a misdemeanor or felony in your past and have turned over a new leaf, your options for tools are severely limited.

Dishonorable Mentions

These are truly the worst of the worst, as far as I can tell. Phil Elmore gets a lot of shit online, but he was right to call out these items for being what’s wrong with women’s self-defense.

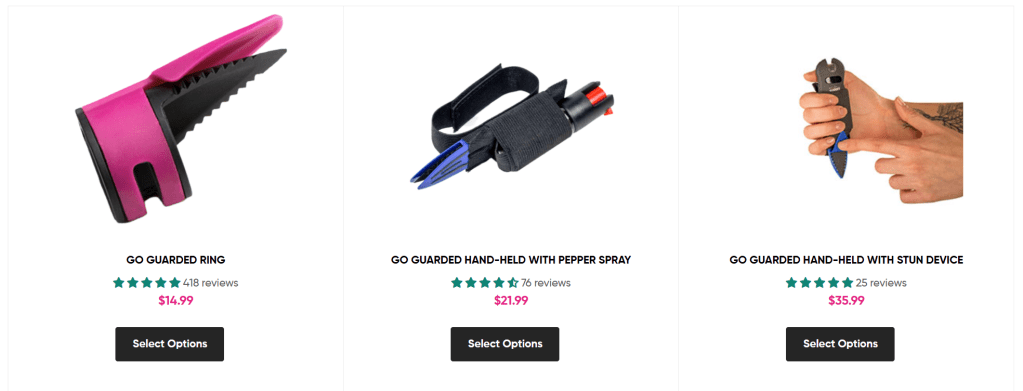

Go Guarded

This company’s flagship product is a serrated ring dagger with a flexible, soft plastic blade cover. It’s meant to be worn on the index finger and used to scratch people, I guess? That’s just conjecture, though, because the actual product description says absolutely nothing about how to use it. One post on the website’s ‘blog’ (I use scare quotes because every maker of anything now needs to have a section of their site to upload vapid, AI-generated text rather than value-added content) reads, “Not only does it have a sharp point, but the sides of the blade are also serrated and are designed to be used in a swiping motion.” Another simply says it “can make your strikes more effective.” We’re left to deduce that the Go Guarded ring is meant to be used kind of like a push dagger.

If your first reaction to seeing this was, ‘that looks like a quick way to break your finger,’ so was mine.

They also sell the Go Guarded Hand-Held, which is basically a nonmetallic fixed-blade knife with an elastic wrist strap; they sell it paired with the usual twist-top pepper spray and generic “stun device” as well as on its own. Like the ring, it’s made of glass-reinforced nylon. Of course, there is zero mention of the fact that shanking someone with one of these would almost certainly be considered lethal force. Now, with a size and strength disparity, that could be 100% justified against an unarmed attacker, but how are consumers supposed to know that? Even a canned ‘know your local laws’ blurb would be better than nothing—it would be something to clue buyers in that there’s more to know.

Go Guarded’s marketing copy stresses that their products are less likely to be taken from and turned against their users—allegedly because of the wrist strap, in the case of the hand-held, and because the ring is, well, a ring.

This is not a totally illegitimate concern even for more skilled self-defenders with more effective tools. It’s easy to say ‘just don’t let them get close enough to take it away from you,’ but harder to do. Side note: much like ‘just stand up,’ or ‘just don’t go places without your gun,’ a recommendation that includes the word just, in the realm of self-defense, is probably one to be disregarded.

So, worries about being disarmed are understandable. Still, this is something of a dog whistle that lets us know the product in question is being marketed to an unskilled, low-information end user who believes it’s more likely they’ll hurt themselves with a protective item than effectively defend themselves with one.

“Hold on, Christian!” Say my totally hypothetical readers. “Don’t those types of users deserve a low-liability, intuitive way to protect themselves, too?”

To which I would reply, of course they do, reader. It’s called pepper spray.

TigerLady

TigerLady sells sets of extendable plastic claws with “channels on the underside…designed to capture DNA so you don’t have to see your assailant to make a positive ID.” They’re meant to “[enhance] your ability to scratch an assailant and quickly get to safety.”

This is a real thing that they charge people real money for.

The best part is the product description, which states, “just the act of holding TigerLady in your hand will ensure that you have a heightened sense of your surroundings.” At first, I thought this was just a cheesy, spur-of-the-moment rhetorical flourish—situational awareness has become something of a buzzword, after all—because it makes no sense. Life isn’t a video game where equippable items give a buff to a perception stat. But, no: it turns out that this is actually a conscious branding decision. The How It Works page doubles down and says the TigerLady, “will facilitate a heightened sense of situational awareness.”

Normally, people are tempted to try and solve software issues with hardware, but TigerLady is actually trying to do the opposite: solve a mindset issue with a product. I guess the tangibility of a physical item in your hand could be a good reminder to stay alert and engaged with the world, but it’s still strange to make that a selling point.

But, I must admit, if I was restricted to carrying nothing but the TigerLady, I would definitely be more switched on than normal…Mostly because of the acute awareness of being utterly naked of tools that stood a chance of stopping an attack.

Conclusion

There are a few takeaways from this post that bear repeating:

- Less-than-lethal tools should ideally avoid causing not only death but serious bodily injury.

- Being gun-shaped is a serious drawback for defensive tools that aren’t guns.

- Self-defense products ‘disguised’ as something else are to be avoided, whether it’s lipstick or pen pepper spray or cell phone stun guns.

Special thanks to Caelan and Wendy for inspiring this series of posts.

What topic would you like to see me cover next? Let me know in the comments.

Thanks for reading!